This is the story of a love story that has a brother, a sister and a smartphone. One of them dies.

The story has a river of fire, which a true lover must drown in, in order to prove his love. And if you like connecting the dots, there’s also Sita, eulogised for her purity, which she proved in an agni pareeksha.

The story exists as much in the virtual cities we build as in the physical cities we run from.

The mythopoeia of fire and love collides in this short fiction inspired by field reports from a rural media channel. Set in erstwhile Faizabad, lacing it with the legends that keep it alive, especially in our news feeds and our smartphones, this is the story of its resident twins Ruhani & Ayub, a brother and sister so close in spirit, yet so different in action.

We revisit the fables we’re familiar with, from the epics to Bollywood, and watch their lives unravel, as they finally come together to fuse identities on a phone screen.

The city of Ayodhya bears witness to these siblings’ lives, and of course, moves on.

What is left is the brother’s voice. And his tale of revenge.

Today, I’m Raveena Tandon.

Not the Andaz Apna Apna and Kabhi Linking Road one (cute, goofy), or the Tip Tip Barsa Pani and Cheez Badi Mast one (sexy, hot, desirable). Oh how these movie stars manage to go through so many avatars through their brief eras, and yet leave a supernova-like impact on our hearts – explosive!

Like Manisha Koirala, and Divya Bharti. Or my all-time personal favourite Amisha Patel. When she does the shimmy-shakes on that deserted island, who doesn’t want to say Kaho Na Pyaar Hai?

Zubeida Khala once forgot a Bollywood filmi gossip magazine at our place. Having convinced Ammi that it was a good way to practise our English, I got my hands on it. I read a phrase in it that has stayed with me ever since; evocative of the drenched yellow-sari-clad Raveena it was describing, but also life, ambition, victory.

The phrase is ‘oozing oomph’, and I’ve always wondered what it would be like to ooze oomph. For my experiment in revenge that begins today, Raveena’s rain-soaked sass suits me just fine.

But I get ahead of myself.

First you must meet her, she whose voice I’ve been hearing in my head, in all its sweetness, calling out to me, “Ayub Bhaijaan.” I could be in Delhi at work, or back home in Faizabad, but the voice hasn’t left me, like she did. Perhaps because we’re twins, or perhaps because that’s just so Ruhani.

Our family lives close to that godawful, dare I say godforsaken, piece of real estate that is almost always in the news – screaming on the front page, as if demanding a blood sacrifice. Of late, it has become a trending subject almost everywhere – chai dhabas, panwaris, trains and buses – screens spewing venom and outrage on one hand, while sharing images of a world record-breaking number of Diwali diyas on the other. The spot itself where they laid the foundation for the much-awaited place of worship is about four-odd kilometres from where we live, as the crow flies.

It’s one of many expressions Ruhani taught me – as the crow flies – continuing to teach herself English even as I gave up. I can see her now, pausing yet another video and repeating words and sentences and phrases to herself, slowly grasping a new language alien to most around us.

Baba would almost always admonish her, “What will you do learning all this? Kahaan kaam ayega?”, and Ammi would proceed to cast off the evil eye on her English-speaking daughter.

It was Ruhani who informed me that faces darker than mine – so dark that they went over to the black side, from the more respectable ‘wheatish’ we often used in descriptions for matrimonial advertisements – spoke “perfect American” on YouTube. When she first showed me some of them, these men (and women!) who looked like us – performers in their own right, either onstage telling jokes, or in studios on news panels, also telling jokes, you could argue – and then opened their mouths to say things in that distinctly American way, I almost fell off my chair!

It was Ruhani who would often be found jaunting around that area cordoned off on good days by surly-looking cops and vibhuti-sporting sadhus. The Hanuman Garhi market, a short walk from the famed janmabhoomi mandir, is where she would often go after class to meet up with her boyfriend. That horrid Mohit. She would end up buying bangles and they would share cotton candy before walking back home, in separate directions. She thought I never knew her secret, but I always did, I just never said anything. Not even when she begged me for my phone “just for one hour” one of those holidays I was back home. Independence Day, maybe? I seem to recall many flags dotted over Tarun Bazar block where we live, atop homes and shops and even motorbikes, tricolours and the more recent all-saffron ones.

Since then, Ruhani’s phone-borrowing became an undeclared ritual between us, and I was more amazed than annoyed at how she managed through the long interims of time when she presumably had no access to WhatsApp. I never confronted her with the secret, because she looked genuinely happy, which is more than I can say for Abbu, Ammi, or even myself.

And with me working in Delhi, she’d probably assumed that her benevolent Bhaijaan doesn’t know much. On my part, it really only took a few texts and a missed call from Mohit one fateful night when I had meant to go home but couldn’t at the last minute because Gupta Saheb had to suddenly take his family for a long weekend and the other security guard was down with swine flu. Mohit had assumed the phone was in Ruhani’s soft hands by then, and even though I didn’t officially have a girlfriend, I knew what those strings of emojis meant.

Next time I was home and Ruhani came up to me, with that familiar expression of I’m-just-about-to-ask-a-favour-of-you, I gave her a knowing smile in return. She was taken aback for a moment and then her mood changed – her eyes always gave her away, and I saw in them, for the first time, confusion and also a hint of fear. I think she might have been willing to give up her promised, much-anticipated midnight WhatsApp video call despite herself, until I fished out what I’d bought her. “Your Eidi,” I said, handing the box to her, and even before she could react, I added, “Can you show me some of those Americans on your YouTube on this?” At ease, her grin reflected mine, and ripping off the wrapping I’d inexpertly stuck together back in my room in Adhchini, south Delhi, she responded, “Yes. Right after a few Raveena Tandon videos, na?”

I almost told her then about my own little secret. How I had discovered the ultimate time pass that surpassed the YouTube rabbit hole, because it tasted of blood, just a wee bit.

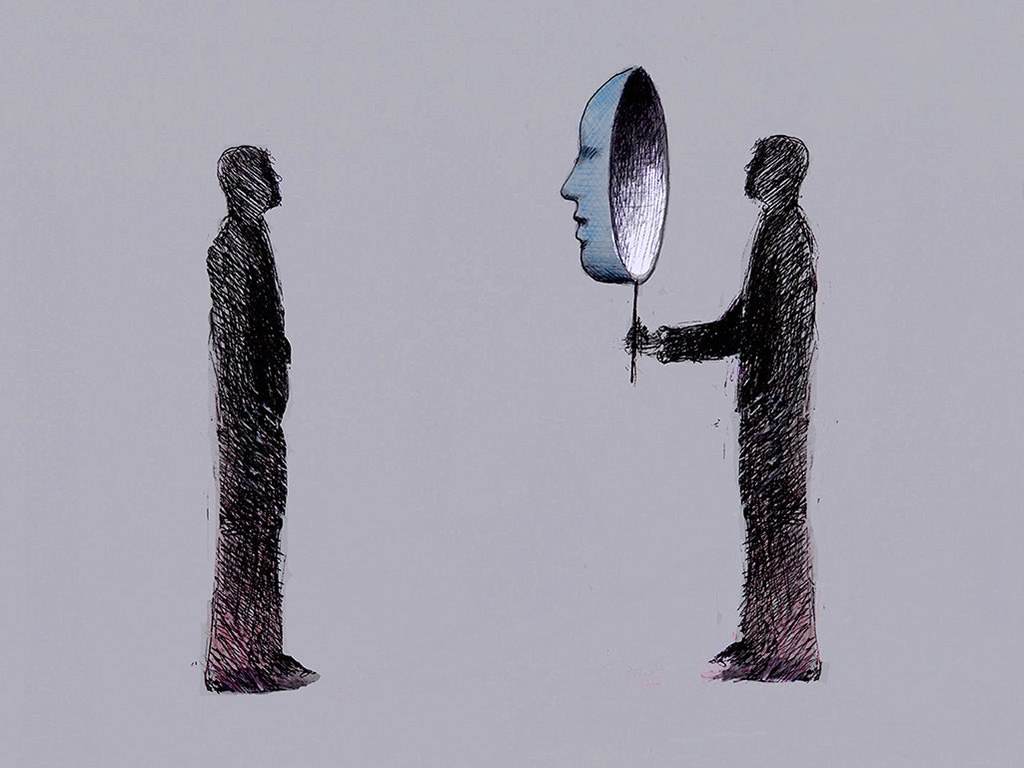

I would spend hours upon hours teasing boys on Facebook and WhatsApp with fake profiles, pretending to be a girl.

I even knew some of them from back home, and wasn’t at all shocked when all of them sent the maximum number of DMs to the SIM card that was Neha – I’d bestowed upon her the precious Amisha Patel DP.

What did unnerve me, but only slightly, was the nature of the messages the boys sent me. Although most of them wanted to ‘make the friendship’, and some were interested in real-life meetings, all of the men had umpteen comments on my physical appearance, which they would type into their phones unabashedly. These ranged from lusty compliments to possessive-lover advice. “Aapke rose-pink cheeks ko kahin nazar na lag jaaye. Touchwood (May no jealous eye fall upon your rose-pink cheeks)”, “My girl rocks salwar kameez only”, “Thoda araam se. Aap bholi hain, aapko nahi pata ladke aajkal online mein kya kar rahe hain (Go easy. You’re so innocent, you have no idea what boys are up to online).” This last one had come from a guy roughly my age, he’d gone to school with me for three years straight; he had inherited his father’s mobile repair shop, but hadn’t taken over the reins yet, trying his luck with local politics instead. Easier, more lucrative, but needs guts.

The family and our ‘well-wishers’ all blamed me when it happened. Slapped me with those truisms everyone seems to live by and never questions. Older brothers are meant to protect, discipline, reprimand, command, their younger sisters. Teach them a lesson when required. And look at this Ayub, he bought her a phone instead! Might as well have taken her to the brothel himself.

Did you know Mohit, Ammi asked me again and again. But what could I have replied that might have rung true? I didn’t know him, but I knew about him.

Of all the versions of the story I have heard since, the one that falls into place just right paints Mohit villainous. Or maybe not villainous, because that lends him gravitas.

No, Mohit’s actions, if you could call them actions, were downright cowardly. Couldn’t he have talked Ruhani out of it? We all knew the masjid judgment was due anytime. The bylanes of their favourite hangout were thronging with cops that month and they came by the dozen every single day, filing out of the jeeps, armed with riot gear. “Who knows, maybe they’ll declare Emergency, and seal off the entire state?” some panicked. “At least we’ll still be a State,” mumbled Ruhani. Abbu had refused to step out for days when he first saw the riot police trickling in, it was an achingly familiar sight, he said; speaking to him, you’d really think the 90’s happened just yesterday! I understand his pain having lived through that time when he had to shut shop and flee to ensure the safety of his wife and daughter – there had only been the new-born Najma Baji then – and coming back to pick up the pieces of a life he once had, but sometimes I just want to tell him to get over it! But even so, Abbu’s is a real fear, whereas Mohit’s was not from lived experience. Couldn’t he have played his majority card instead of simply running away?

If I’m honest, I know better than to blame him. Ammi can say what she likes, beat her chest about losing a daughter again, and not fully absorb what the reporter who came to meet her was suggesting.

I could see that reporter writing the click-bait headline in her head – Woman Loses Daughters to Social Evils, One to Triple Talaq, One to Love Jihad – even as she was pretend-comforting Ammi, her sunglasses perched atop her head, like some of those American-speaking people on Ruhani’s YouTube.

In the moment, I wondered about Najma Baji; would she have taken her own life if Ammi and Abbu hadn’t turned her away when her in-laws had thrown her out for reporting their son under the newly-formed Muslim Women’s Marriage Rights Protection law? “You must adjust in your marital home,” they had said to her. I retched my guts out now recalling this even though I had never been close to Najma Baji.

Not like Ruhani and I. Born a few minutes apart – me with my two and a half minutes lead on her! – Ruhani had always been like another me, to me. Except stronger, feistier, funnier, braver, more oomph-oozing you could say. I know this, and so I know that Ruhani’s murder – the new term is lynching, though it’s never been used for a woman and hasn’t involved burning someone, I’m told – was not Mohit’s fault.

If Ruhani had made up her mind about something, nothing and nobody could make her change it. Abbu rued her birth and his luck many a time because of her stubbornness. “Aafat,” he would mouth on good days, and “Shaitan ki beti,” on bad ones.

It never did deter her, Ruhani liked being aafat. When she decided to take up a computer course, she urged the nearest cyber café to put it together for her. When she decided to attend that police training workshop in an adjoining district, she made me say yes to accompany her to it. “It’s only 62 miles away,” she’d said, grinning. On the way back, we’d stopped for sticky gud jalebis, and she’d reminded me of that Govinda-Karisma song about eating roadside snacks and not giving a damn what the world thought. In the bus, she’d started singing the song too, even though we both noticed our neighbour from five houses down glaring at us. Days later, Ammi had admonished us both, with a long story about how she’d placated that Aunty who’d seen us shamelessly singing, “She’s just moved here, so she doesn’t really know you, Ayub. She thought Ruhani was with some boy, gallivanting across cities, eating jalebis! Imagine that!” Ruhani, I’m certain, had only been half-listening, even though she giggled about it later. “You’re so handsome Ayub bhai, Aunty ji must have been jealous!” she’d teased.

After all that, she’d finally decided to sit for the civil services exams. “Women cops are not given promotions,” she reasoned, “and not taken seriously,” explaining away her last wish at a career. “Becoming administrative madam has its own impact.” A few stray comments in Hanuman Garhi one evening in the run-up to the 2019 verdict had urged her, she’d told me.

“Everybody makes it about religion, but it’s actually about governance, isn’t it?” If you could heal the system from the inside, there was hope, she believed.

She was Sita on these groups – a political choice of course, but also because she knew that her religious identity would be a far greater burden to carry online than her gender – the self-appointed fake-news buster offering video tutorials on spotting doctored clippings.

The voice of sanity and reason and goodwill determined to break through the clutter and noise.

She would spend hours teaching herself reverse image search and other hacks she found on YouTube and then apply them to the fantastic fiction that floated around on Whats App, masquerading as ‘real news’. She would share her findings on the groups she’d become part of with just the right dose of provocation. Or at least that’s what she thought. Of course almost everyone assumed, I think, that Sita was in fact, a man. It was such a given truth. Almost everyone.

A cousin of Mohit I’d met in that dazed week that had followed Ruhani’s murder, told me how a mob of young men had come banging on Mohit’s door late into the night, demanding that he hand over his phone. They were drunk and enraged at his choice of prospective life partner. “Aar ya paar ka time aa gaya hai (The do or die moment is here). Which side are you on?” they had bellowed. But what had frightened Mohit, the cousin had told me, was that while he had recognised most of the men as pals and acquaintances, he could not see even a hint of recognition in their eyes. The leader of the bunch had immediately opened Mohit’s WhatsApp to check his messages, and confirmed the identity of Ruhani-Sita.

Soon after, Mohit fled. The hometown where he’d dreamed of starting a small business of his own someday, and in some world, perhaps even seeing his relationship with Ruhani come to fruition.

I imagine him now, bidding farewell to the Sarayu, brooding on the ghats.

Perhaps he didn’t though. By his cousin’s reckoning, he must have taken the bus out of town that leaves just as dawn breaks, careful to not step out of the shadows. Probably already thinking about which phone he would buy, a new SIM card in his pocket. Maybe wiping away a few tears in the dark as he boarded the bus.

For Ruhani-Sita though, she who strode under the bright sun, the walk across the fire of truth turned out to be unforgiving in the end. It did not leave her unscathed, far from it.

Nor did it leave me unscathed, the silly man who could never stand up to anything and chose to walk out of the small town that stifled one and all, only to play Guard Bhaiyya to the posh and rich of the country’s capital. Who was foolish enough to gift his sister exactly what she wanted, a smartphone, a weapon of mass destruction no less. I will carry the scars of her burns too, forever.

And today I decide, I will take on her legacy.

I scroll through my WhatsApp and ask a few friends to add me to those groups she’d been on. I juggle a few SIM cards, take on a fake identity, and decide to apply all that learning I have assimilated in jest, to while away long duty hours.

I will continue playing another version of Sita on her behalf, in her memory.

I know what they want, and I will give it to them.

I will ooze oomph forever.

For DP, I’ll go with Raveena Tandon. Paani ne aag lagayi.