Hyderabadi women have been writing in Urdu since the second half of the 19th century. This in itself is not unusual; for, women in other places as well, such as Bengal and Bihar, were writing around the same time. There are historical reasons for this development, which I will describe later in this account. What I want to highlight at present is that there is an unbroken 150-year-old tradition of Hyderabadi women’s prose in Urdu, about which we know almost nothing for very specific reasons. These reasons have to do with what I have elsewhere called the triple marginalisation of Hyderabadi women writers of Urdu.

First, Urdu is not a language we associate with the South, which is ironic, given that it was in the Deccan that Urdu grew and developed as a literary language from the 15th to the 17th centuries. While the Northern royal courts preferred and exalted the cultural capital of Persian 1, it was in the royal courts and Sufi shrines of the Deccan that this Urdu—which became known as Dakhni—blossomed and thrived. As Shagufta Shaheen and Sajjad Shahid have pointed out, it became a literary language that was no different from the link language people used in the bazaars and streets. In other words, aam zubaan (the people’s tongue) and adabi zubaan (literary language) were the same. This is different from the way literary Urdu would develop later in the North. Despite the blossoming of Dakhni as a literary language in the Deccan, it is the North that we associate and credit with the development of Urdu, and it is this Northern Urdu that is perceived to be the standard language to which other regional iterations of the common tongue have come to be subordinated. This is because of the Mughal conquest of the Deccan in 1687 and the subsequent establishment of Asaf Jahi rule by the Nizams (1724-1948), which displaced Dakhni and emphasised the superiority of Northern cultural capital, including Northern Urdu. Significantly, Dakhni and the other ‘Urdus’ of the Deccan are not easily accommodated in the South either. Despite the rich vocabulary and image universe Dakhni draws from languages such as Marathi, Telugu and Kannada, it is seen in the South as a lesser cousin of a Northern language.

The second reason that we do not know much about Hyderabadi women writers of Urdu proceeds from the relatively little research on the society and culture of princely states. This is an astonishing oversight when one considers the fact that at the beginning of the 20th century, the Indian subcontinent was home to 565 princely states. This neglect can be traced to the self-serving colonial assertion that it was only in British India there was social progress and a cultural life to speak of, ostensibly due to (what was represented as) the benevolence and enlightenment of colonial rule. The princely states, on the other hand, were seen as frozen in time, static and timeless, where medieval potentates ruled over an Orientalist fantasy. This stereotype has endured for long, much to the detriment of scholarship and the histories of individual princely states, leading to a sustained perception that a public sphere was nonexistent in the princely states. It is only recently that a concerted effort has been made by scholars such as Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Janaki Nair, Kavita Saraswathi Datla, Razak Khan and others to study the individual princely state and its culture and society.

Finally, the marginalisation of Hyderabadi women writers of Urdu can be attributed to gender. Urdu literary historiography in both English and Urdu not only more or less excludes Urdu writers from the South, but further sidelines women writers. Occasionally, Mahlaqa Bai Chanda (1768–1824), a remarkable taifa or courtesan from Asaf Jahi Hyderabad, may find mention in such histories. Research has shown how tawaif were an important and prominent group of literary women. They composed poetry and set it to music and dance and were influential players in the intellectual, literary, and often even political cultures of their time.

This is not to say that other women did not write. They probably did, and evidence suggests that apart from royal and noble women, women from Sufi families—i.e. women who would have had some access to education—have produced works of poetry. Amena Tahseen has also pointed out that our reliance on writing and textual materials as evidence of literary activity among women has prevented us from considering oral traditions as representations of a much longer history of women’s verbal creativity across class. So, courtesans were certainly not the only women composing poetry or putting words to song. But their public visibility ensured that they are the most prominent group of literary women that we are aware of before the mid-19th century. No further mention is made of the poetry produced by women in the Deccan. About their prose, we know even less.

The magnitude of this gendered neglect in literary historiography becomes clear when we realise that there were no fewer than 150 women poets known to be from the Deccan and writing at different points in time.

We know of this number through the work of Nasiruddin Hashmi, a scholar who strove to address the lacuna in recording the literary accomplishments of women in the region and wrote several volumes about the women writers, poets, and patrons of the Deccan. Hashmi also wrote useful biographies and ethnographies of women writers, reformers and patrons in late Asaf Jahi Hyderabad, which have become invaluable sources for literary historians.

Reform and education in the 19th century

Women were central to this bourgeois cultural project because of their role as the bearers of future generations as well as guardians of the culture of their communities 4 . So it was thought to be imperative that they should be educated 5 . Among the early schools founded by non-mulkis was the Hindu Anglo-Vernacular School, established by Aghorenath Chattopadhyaya in 1881, where 76 Hindu and Muslim girls — including his own daughters, one of whom was the future Sarojini Naidu — studied 6 . But whether they were founded by non-mulkis or mulkis like Nurunnisa Begum, these early schools, which were run in their founders’ homes, were short-lived because they were usually intended only to offer a new kind of education to family members.

It was the associational work and writings of middle-class women and men of ghaer-mulki origin that played a vital role in championing girls’ and women’s education as well as the relaxation of pardah norms 7 . Literary journals were the main catalyst in this regard.

In the fullness of print

Tayyaba Begum was the daughter of Syed Husain Bilgrami, Hyderabad’s Director of Public Instruction, who had made such a place for himself through his service to the cause of education in the state that he was awarded the official title of Imad ul-Mulk (Pillar of the State). Like other women of the Bilgrami family, Tayyaba Begum was educated at home and went on to complete her FA and BA by studying privately after her marriage in 1896. A mother of four, she became the first Muslim woman to complete her BA in 1910 and wrote two novels in her lifetime 10 . Of these two, she is known for Anwari Begum, which was serialised in Ismat in 1909 and published as a novel only after her death 11. A reformist text that underlines the importance of a modernised Muslim education and condemns superstitions, rituals and the strictest forms of pardah, Anwari Begum centres on women’s lives and perspectives, which was uncommon at the time, particularly because contributions to the reformist discourse on the part of male reformers usually saw women’s lives in terms of their roles and responsibilities towards their husbands and families alone 12 .

Pardah clubs and associations

Tayyaba Begum and Sughra Begum were also prominent among the Hyderabadi women who were invited to speak by other associations or organisations, both in the state and outside 15 . At these events, Tayyaba Begum initially spoke of the need for an education beyond religious instruction that made women equal and viable companions for men 16 . Over time, her speeches reflected her evolving views, and she began to speak of the needs of different classes, stressing the necessity for women to earn a living as teachers, doctors or typists. She and Sughra Begum spoke against the rigid practice of pardah they saw around them and argued that it was, in fact, preventing women from fulfilling their educational, cultural and religious obligations 17 . Both were practising Muslim women who framed their thought about gender and society through religion. Harmony between faiths and sects was a matter of great urgency for both. In one speech, Tayyaba Begum thoughtfully argued that

“Bigotry, whose foundation lies in ignorance, is a destructive force … trees too have such a disease which cuts a tree down or hollows it out at the roots. Similarly, bigotry is like a white ant that demolishes the foundations of religion … When the healing ointment of amity and unity is applied, this disease will surely be cured. It would be unjust to lay the blame on any one party for bigotry. Everyone is responsible for it 18.”

The discourse on women’s education evolved gradually in Hyderabad and elsewhere, and in 1943, when Hashmatunnisa Begum delivered her presidential address at the women’s meeting of the All-India Muslim Educational Conference in Aligarh, she emphasised that the country needed women teachers, doctors, nurses, and midwives, and underlined the necessity of preparing girls for the changes that lay ahead for the country and for them 19. Hashmatunnisa, who was born into a Paigah noble family in Hyderabad, was herself a product of the Mahbubia School (f.1909) in Hyderabad and had gone on to start girls’ schools and maternal care facilities in the state.

Women were also active in managing and financing journals and newspapers towards the middle of the 20th century. The communist activist, Jamalunnisa Baji (1912–2009), for example, risked her own future as well as her son’s already meagre inheritance by investing most of the funds she had received after her husband’s death in Payaam, a left-wing newspaper taken over by her brother, Akhtar Hasan. Sakina Begum, a daughter of Tayyaba Begum, served on the board of Sabras (1938), and to her is attributed the significant number of literary and research essays by women that were published by the journal, as well as a special women’s number titled Nazr-e-Dakkan, which contained articles on women’s poetry and prose 20 . The Idara-e-Adabiyat-e-Urdu, which published Sabras, was keen to draw women contributors and readers to the journal in order to fulfil its objective of promoting Dakhni. In fact, one section of the Idara’s library was dedicated exclusively to women patrons and their research and publishing activities 21 .

Sughra Humayun Mirza: An institution

Tayyaba Begum lived a relatively short but productive life, publishing works of fiction and non-fiction and contributing in vital and influential ways to the long-term discourse and promotion of girls’ and women’s education in Hyderabad and elsewhere in the subcontinent. She died of cancer in 1921, leaving her younger friend and colleague, Sughra Begum, to further her initiatives and objectives. Sughra Humayun Mirza was an institution in her own right. She came from a ghaer-mulki family and was born to Mariam Begum, a renowned scholar of Arabic and Persian, and her husband, Captain Haji Safdar Ali Mirza, a surgeon in the Hyderabad Army. At 16, she married Humayun Mirza, a lawyer and reformer. Together, Sughra Begum and Barrister Humayun Mirza made a formidable and dynamic team, both in the world of social reform as well as the general literary milieu of Hyderabad.

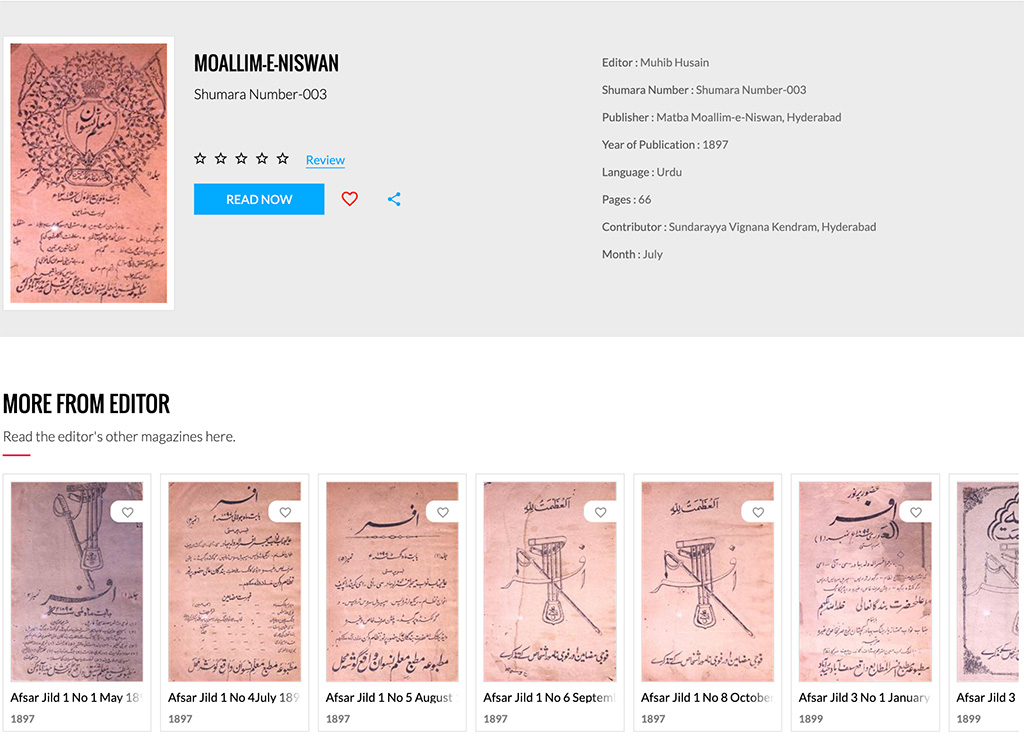

Sughra Begum founded the Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Dakkan, and under its aegis began the women’s journal An-Nisa (1919-1927), which offered creative and scholarly writing, articles on health, homemaking, women’s education and superstition. She wrote many of the articles herself, but also encouraged other women to contribute 22. Following the success of An-Nisa and the growth of associational culture and education among middle-class women, many more Urdu periodicals edited by women and containing contributions by women were published. These monthly or quarterly publications, usually edited by women, included Khadima (1922), the illustrated Hamjoli (1931-1940), the illustrated Safina-e-Niswan (1932), Naheed (1938), Iram (1940), Momna (1941), Khayabaan-e-Dakkan (1941), Hairat (1947) and Iqdaam (1950). They published fiction, poetry, criticism, literary and social essays by women, and a few additionally offered historical, scientific and medical essays and information.

One of Sughra Begum’s most extensive educational projects was the Madarasa-e-Safdaria, which still flourishes in Hyderabad as an Urdu-medium school for students from low-income backgrounds. She was not only involved in its everyday running, but also bought land to build it and left most of her property to it. Besides local and national associations, she was also a member of international organisations where she was invited to speak. She contributed to the nationalist cause through her writings on communal harmony and campaigned for the use of swadeshi goods, and was the only non-Hindu member of the Hindu Women’s Association. Unlike Tayyaba Begum, who observed pardah all her life, Sughra Begum did not, and addressed gatherings of men. She went on to develop enduring friendships and correspondences with writers and political figures, ranging from Rabindranath Tagore and Sarojini Naidu to the deposed Ottoman Sultan and Mahatma and Kasturba Gandhi 23.

The writings of Sughra Begum

Sughra Begum wrote poetry under the takhallus (pen name) Haya, and is believed to be the first woman novelist from Hyderabad, producing no less than 14 novels, of which a few have survived 24. As many scholars have rightly argued, the form and substance of her fiction must be understood in the context of her activism, for Sughra Begum was first and foremost a reformer. The aim of her writings was to influence social change, which shaped her fiction in striking ways. Her novel Mohini (1929), for instance, depicts the eponymous protagonist, a princess, who has given up her inheritance, setting out on a quest for Truth. One of the significant moments in the text is when Mohini dreams of a discussion among the leading reformers of the day on contemporary questions in relation to women’s rights, such as in the context of divorce and remarriage. The text thus traverses two different forms of story-telling, exhibiting both characteristics of epic fantasy and fairy tale as well as elements of social realism.

Scholar Ashraf Rafi has identified Sughra Begum’s many qissas and kahanis as early examples of the Urdu short story (afsana) 25. Qissa and kahani are older forms of storytelling and performance in the Urdu-Hindi continuum. Qissa, for example, consists of epic storytelling containing cycles of fantastic tales. These older forms of storytelling are not bound by realism and are characterised by an episodic and anecdote-driven structure, dominated by dialogue. Some of Sughra Begum’s novels, such as Mohini, follow similar patterns, with stock characters and episodic structures, and demonstrate no particular concern with maintaining the verisimilitude and plausibility that we have long been accustomed to in the novel genre, irrespective of whether it is a realistic novel or a fantastic one.

Sughra Begum’s fiction reveals two interesting features. First, it belongs to a still relatively early stage in the development of Urdu prose, where writers relied on older oral, performative narrative modes in the subcontinent—such as qissa or dastan—while trying their hand with these western genres, which had become more accessible and, in some ways, inevitable for Indian readers and writers as a result of the colonial encounter 26. Humaira Saeed argues that the first women novelists wrote their novels for women alone to read and feel inspired to improve their lives 27 . This is why we must not dismiss Sughra Begum’s particular style and manner of writing in her novels as “fictionalized preaching” 28 . It is easy to read writings by reformist women in this manner and risk overlooking the specifics of their aesthetics and objectives. In this regard, Rafia Sultana and Tahseen have argued that standard criteria used to assess novels and short stories—which, in any case, stem from Western/Eurocentric contexts—cannot be used to characterise early prose by women writers, such as Sughra Begum, Tayyaba Begum, or indeed their other contemporaries in Hyderabad and elsewhere in the subcontinent. Because these texts were meant, first and foremost, to inspire reform, they contained elements of the popular storytelling genres and modes with which women readers were already familiar and comfortable 29.

An intrepid traveller

Sughra Begum’s prolific work also includes the five travelogues she wrote between the 1910s and 1920s about her travels within pre-Partition India as well as Europe and Asia. These encyclopaedic, minutely detailed and perceptive accounts of different countries are based on diary entries that she wrote using her running notes as reference. These were published in serialised form in An-Nisa and later compiled into books. Nothing was too small for Sughra Begum’s notice, and her diligence in recording facts and details is remarkable. The workings of a dedicated journalist constantly considering her pardah-nashin reader are evident from the narrative details, explanations and what she chooses to explain in her travel accounts. Safarnama-e-Europe is fascinating, for example, for not only a remarkably discerning and important study of Europe, particularly Germany, between the two World Wars but also its thematic essays, which provide insightful descriptions and analyses of the places she visited that were close to her reformist heart, e.g. educational institutions, maternity homes, orphanages and shelters.

What is also especially revealing is her frank and disarming confession of the toll exacted by the rigours of seeing and describing these places in such feverish and uncompromising detail. Unable to see the Kaiser’s Palace on the same day that she visited a large museum collection in Berlin, she rues:

“I was exhausted … [But] tired or not, write I must. The anxiety to write hounds me

in such a manner that I cannot see anything without worrying about writing. I see things, I write them down then and there. Then I note it all down in my diary when I return home 30.”

On another occasion, she writes:

“Roaming around the room, I was ready to drop with exhaustion. And if I had not had a pen in hand, I would perhaps have enjoyed the excursion. On top of that, I worry that I might miss something, that I should write as I go. That woman would talk in German, and I would write in Urdu. I would find out [what she was saying] from others. In this way, what I wrote, where I found myself [I do not know].” 31

Apart from the personal toll that this arduous process takes on her, what is also significant here is Sughra Begum’s all-consuming desire and anxiety to see everything, find out everything, and miss nothing in her communication to her reader.

There is an intriguing and voracious appetite to this restless quest that severely and critically undermines the hegemonic idea of the traveller—male, European, virile, and energetic, the coloniser—against which both the East and Eastern, particularly Muslim, women have been negatively defined and Othered. Sughra Begum’s pursuit for information, knowledge and understanding is radical and politically powerful and speaks back and inverts the European coloniser’s exercise of power through knowledge. In some ways thus, that hegemonic conception of the traveller and travel writing becomes a foil to the personality and writings of Sughra Humayun Mirza and her insatiable personal curiosity and relentless sense of duty—social, political, and literary—to her readers. The personality that emerges from her account annihilates the silencing and assumed silence of Muslim women as travellers and writers, and indeed restores them to history as subjects with agency.

Women’s College and the persistence of homeschooling

Osmania University (OU) was the first in the subcontinent to offer higher education in an Indian-language medium. It began a massive undertaking of translating reference books from other languages into Urdu in the 1920s and 1930s, producing fresh textbooks on literature, history and religion at this time, and developing dictionaries and glossaries to shore up the resources of Urdu and present it as a viable option for a national language for independent India, as Kavita Saraswathi Datla’s remarkable work has shown. OU is significant for our purposes here because it also boasted its own Women’s College, which was largely the ambition of one woman, Amina Pope, the principal of the Nampally Girls’ School (formerly the Zenana School), who wanted her students to continue their education beyond high school and acquire university degrees.

With support from the state, university-level classes began on the school premises in 1924. By 1939, the number of students in the college’s FA/FSc and BA/BSc courses had risen from seven to 200, and new premises were sought 32. By 1949, the college had so many students it was moved to the imposing British Residency, which had been lying vacant since the departure of the Resident in 1948, and where it is still housed. Women’s College and OU in general provided contacts and connections for women who read and wrote in Urdu and allowed them to become members of a peer group inclined towards writing and activism. These interactions facilitated exposure and opportunities for them to shape social, political, and literary debates and discourses.

Despite the developments in education — such as the establishment of the Nampally Girls’ School and Mahbubia School as well as Women’s College, which was meant for higher studies and the efforts of reformers in changing social norms and practices, many girls from middle- and upper-class families in different communities were partly or wholly educated at home right up to the 1940s. Schooling was uneven and came to women of different linguistic, caste and class communities at different times in Hyderabad’s history. Karen Leonard has pointed out, for example, how Parsi women were already well-educated for several generations before Muslim and Hindu women could access education 33.

Sometimes this homeschooling was indifferent and formulaic and meant to check the boxes of religious instruction, mother-tongue instruction, and some set markers of cultural capital (such as poetry). But in other cases, it could be remarkably rich and varied. Sughra Begum herself is one example, for, her mother, who educated her, was a well-known scholar of Arabic and Persian. Sylvia Vatuk’s micro-history of the family of Zakira Ghouse (1921-2003) reveals another example of home-based education of some duration and quality, conducted by mothers and grandmothers. As we learn from Zakira Begum’s life, even in extremely conservative contexts where girls were restricted from going to school, perceptions were changing by the 1930s, and it was possible to imagine and expect more from life than marriage and motherhood alone. This changing perception, at least among secluded women, appears to partly emerge from the impact of books and journals for women 34. Literary journals and magazines, when they were available, would have been important to secluded girls and women who had otherwise little access to a public sphere. The writings of reformists often formed an important component of this homeschooling.

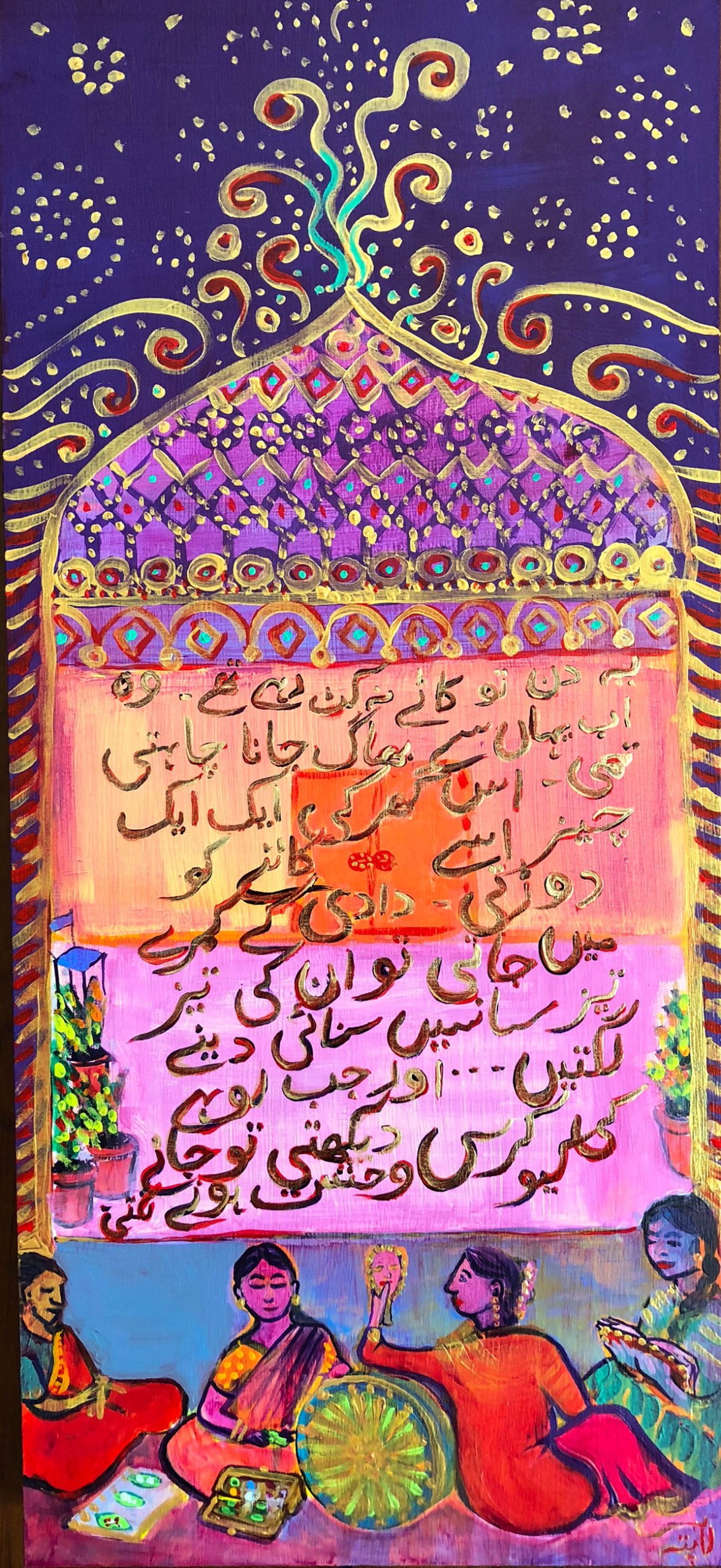

In many middle-class homes, such as those of Jamalunnisa Baji, Zakira Ghouse and Jeelani Bano, it was also common for girls and women to have their own family magazines, which were handwritten painstakingly on whatever paper was available and circulated among family members.

These magazines or newsletters were used to exchange the news of the day and other items of interest and concern to them. This activity mirrored that of associational meetings, where sharing and discussing views and opinions were important activities. In the 1950s, Zakira Begum wrote her memoir to be published in the family magazine in 16 instalments. And as teenagers, Baji’s sisters, Razia and Zakia, who later became professional writers and teachers, began a weekly family magazine called Prime Gazette in which they detailed everything that happened during the week. There was also a monthly called Taameer, which had stories, poetry, reviews, and political, social and literary essays written by the two girls and, occasionally, Baji and their brother Akhtar 35.

- This is not to say that Persian was the only literary language at these northern courts, but that Urdu received greater patronage in the Deccan, which allowed and facilitated its growth along with other literary languages.

- Margrit Pernau, “Female Voices: Women Writers in Hyderabad at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century,” The Annual of Urdu Studies 17, 2002: 40; Sheela Raj, Medievalism to Modernism: Socio-Economic and Cultural History of Hyderabad, 1869–1911, Bombay: Sangam, 1987, 246. It is a mark of Salarjung’s foresight and wisdom that while he had not learnt English himself, he knew which way the wind was blowing and had ensured that English was a part of Nurunnisa’s education.

- Pernau 2002: 38–39; also, “Schools for Muslim Girls – A Colonial or an Indigenous Project? A Case Study of Hyderabad,” Oriento Moderno 23 (84), 1, 2004: 275.

- Pernau 2002: 39. Op. cit.

- However, it is not that middle-class women were totally uneducated before the establishment of schools. Before these early schools, with a few exceptions, most Muslim and Hindu girls would have had some exposure to religious texts and a cursory introduction to culturally significant texts. Wealthy Muslim families hired female teachers who would live in the zenana, teaching their young charges the namaz, Quran, Hadees, Urdu, Persian, sewing, embroidery and other domestic skills. For more, see Laiq Salah, “Hyderabad ke Chand Tehzeebi Naqoosh,” in Amena Tahseen’s Hyderabad mein Urdu ka Nisai Adab: Tahqeeq wa Tarteeb, Delhi: Educational Publishing House, 2017, 287. What schools would bring is greater quality, duration and consistency in the education of girls and women, along with a formal environment in which they could study with their peers and have a sense of themselves beyond their place and roles in their families and communities alone.

- Raj 1987: 245; Gail Minault, Secluded Scholars: Women’s Education and Muslim Social Reform in Colonial India. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998, 205.

- Pernau 2002: 39. Op. cit.

- Ibid. 43; Ashraf Rafi, “Hyderabad ki Afsana-Nigar Khawateen,” in Tahseen 2017: 165.

- Pernau 2002: 36. Op. cit.

- Tayyaba Begum would send all three of her daughters to Mahbubia Girls’ School. The information about Tayyaba Begum’s life in this paragraph has been summarised from Gail Minault’s vital and influential work in Secluded Scholars, 28.

- Minault 1998: 208; K. Krishnaswamy Mudiraj, Pictorial Hyderabad. 2 vols. Hyderabad, Deccan: Chandrakant Press, 1929, 1934, 378.

- Pernau 2002: 49–51; Minault 1998: 212. Op. cit.

- Pernau 2000: 232–33; Minault 1998: 284. Op. cit.

- Pernau 2002: 54. Op. cit.

- Besides the major national Muslim associations, Tayyaba Begum spoke at meetings of the Brahmo Samaj (Mudiraj 379).

- Pernau 2002: 45–46. Op. cit.

- Minault 1998: 211-12, 272; Pernau 2002: 52. Op. cit.

- Rasaail-e-Tayyaba, edited by Sakina Begum, Hyderabad: Idara-e-Adabiyat-e-Urdu, 1940, 165. All translations are mine.

- Nasiruddin Hashmi, Hyderabad ki Niswani Duniya, Hyderabad, Deccan: India Book House, 1944, 35.

- Askari Safdar Askari. “Hyderabad mein Khawateen ki Sahafati Khidmaat,” in Tahseen 2017: 277–79; Hashmi 1944: 74; Kavita Saraswathi Datla, The Language of Secular Islam: Urdu Nationalism and Colonial India, Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan 2013, 128-129.

- Datla 2013: 127, 128.

- Minault 1998: 210. Op. cit.

- Hashmi 1944: 49-52; Mudiraj 400–402; Op. cit. Volga, Vasanth Kannabiran, and Kalpana Kannabiran, Womanscape, Secunderabad: Asmita Resource Centre for Women, 2001, 51.

- Mueen, Rizwana. “Hyderabad ki Awwaleen Afsana-Nigar Khawateen,” in Tahseen 2017: 181-82.

- Rafi 2017: 166.

- M. Asaduddin, “First Urdu Novel: Contesting Claims and Disclaimers,” Annual of Urdu Studies 16, 2001: 78.

- “Hyderabad ki Novel-Nigar Khawateen,” in Tahseen 2017: 193.

- Pernau 2002: 49. Op. cit.

- Rafia Sultana, Urdu Adab ki Taraqqi Mein Khawateen ka Hissa, Hyderabad: Majlis-e-Tahqeeqaat Urdu, 1962, 101–02; Tahseen 2017: 142-43.

- Sughra Humayun Mirza, Safarnama-e-Europe, vol. 2, place unknown: publisher unknown, 1925, 36.

- Ibid., 62.

- Khatija Akbar, A Teacher’s Tale: Miss Linnell of Mahbubia Girls’ School and Welham Girls’ School, New Delhi: Roli, 2007, 64; Volga et al. 2001: 64; Hashmi 1944: 66.

- Karen Leonard, “Women and Social Change in Modern India,” Feminist Studies 3 (3/4, Spring–Summer): 1976, 128.

- Sylvia Vatuk, “Hamara Daur-i-Hayat: An Indian Muslim Woman Writes Her Life,” in Telling Lives in India: Biography, Autobiography, and Life History, eds. David Arnold and Stuart Blackburn, Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004, 158.

- Jamalunnisa (Baji), Bikhri Yaadein, Hyderabad: Idara-e-Fikr-o-Fan, 2008, 81.