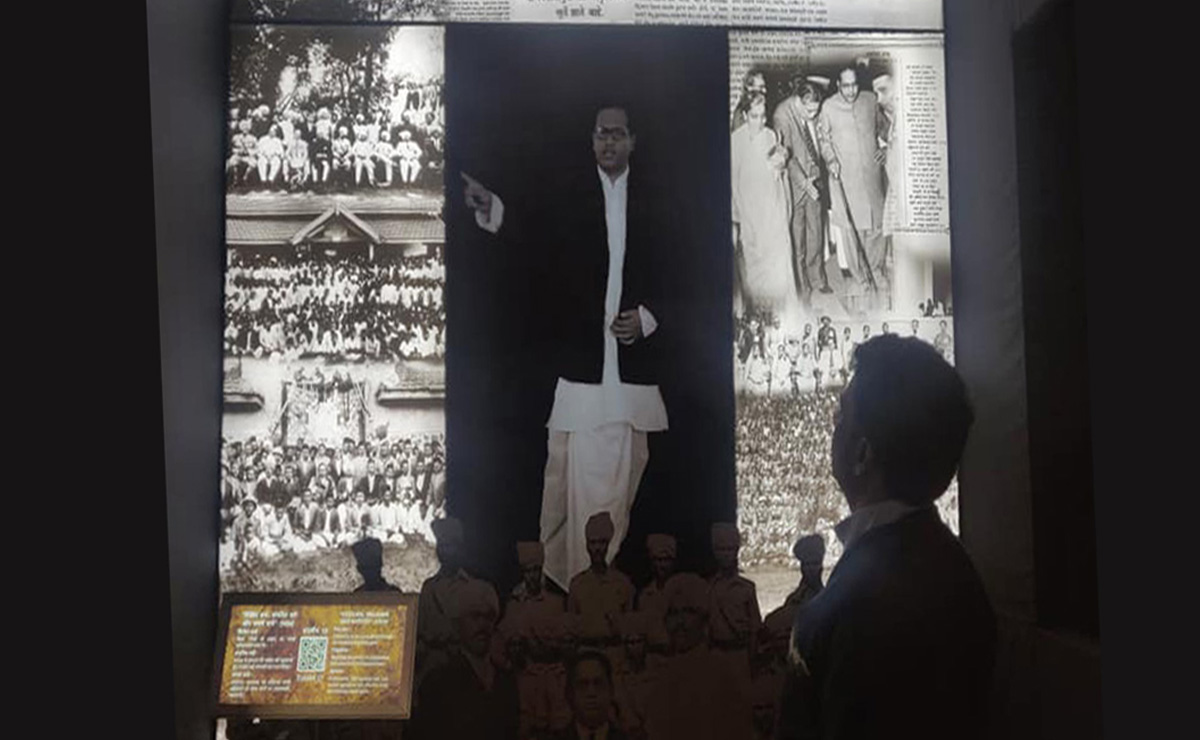

On Dr. Ambedkar’s 131st Birth Anniversary, The Third Eye asked a few professors and teachers about how Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar influenced their teaching.

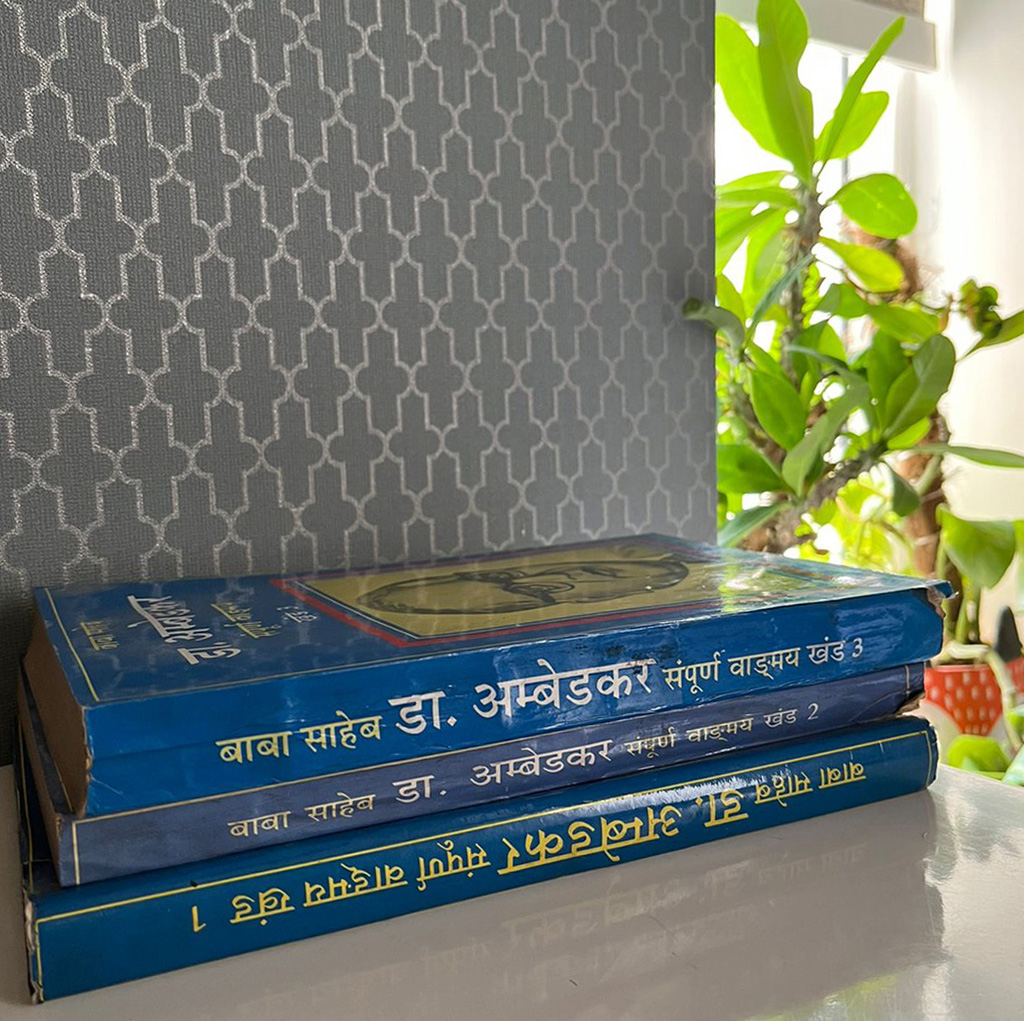

As we remember Babasaheb, we also pay a tribute to his political thought, philosophy, history of collectivising and academic work, all of which continue to shape consciousness of minds both young and old, in and outside the classroom.

Babasaheb’s work and teachings still inspire and remain relevant in these times where we are witnessing shrinking of academic spaces, posing new challenges to public education. He reminds us of the necessity and importance of making institutes of higher learning accessible and conducive to people from marginalised social locations, and gives us hope to fight for our right to public education. His work also reminds us that one of the primary works of education, no matter the discipline, is to draw connections between caste, patriarchy, capitalism and labour.

Jai Bhim!

1

I grew up with an Ambedkarite consciousness since childhood. My mother and grandmother, who couldn’t study themselves, would often invoke Babasaheb and tell me to get a good education. I had always wondered—why are women from our community domestic workers? Why are the people from only our community manual scavengers?

Earlier, I used to think that the lack of literacy in our community is what caused poverty. But engaging with Babasaheb’s political thought helped me draw connections between migration, caste, capitalism and livelihood. My collective would also hold joint programmes with the Women’s Studies Centre, Savitribai Phule University in Pune, where I came in contact with Sharmila Rege and her work.

We used to distribute booklets and other anti-caste pamphlets in schools and bastis and perform street plays. When I started teaching at the Women’s Studies Centre at TISS, Mumbai in 2009, Ambedkarism helped me understand how caste Hindu society comprises division of labourers, not labour; and how when we talk of sexual division of labour, it is important to define patriarchy as caste patriarchy because gender is also constructed through the ideology of Brahminism.

– Dr. Sangita Thosar from Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, TISS Mumbai

2

3

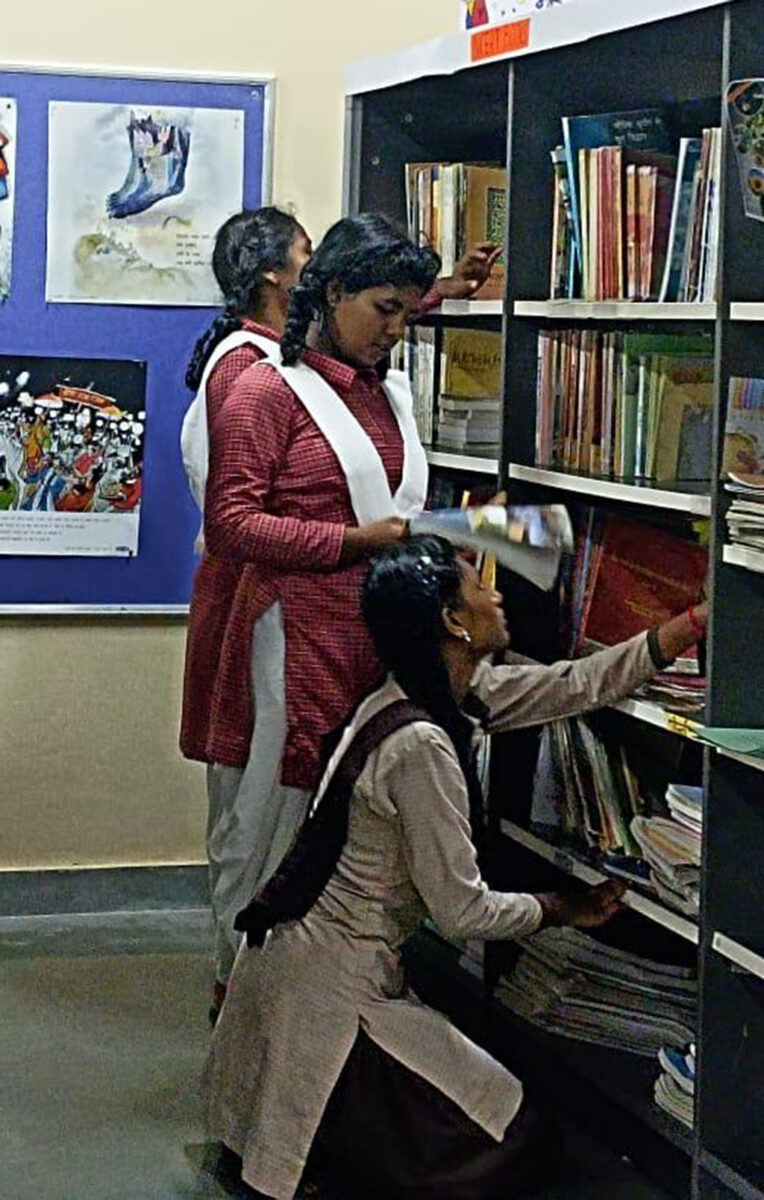

As a Savarna woman, I got introduced to Phule-Ambedkar in the real sense very late in my life, well into my 20s. But reading and understanding this anti-caste thought was like a searchlight switching on and things becoming clearly visible, coming into sharp focus.

Dr. Ambedkar’s ideas on the need for social equality have guided my teaching since. The way he links the need to educate, organise and agitate has helped me see the higher education sector as an embattled one and pushed me to align myself with struggles and politics of social justice whenever possible.

Most importantly, Ambedkar has helped me see myself and my social location with a critical eye, reflecting on my privilege and asking tough questions about what my caste location opens up for me and at whose cost.

This question of power, privilege and reflexive politics has been central to what I try to do in the classroom. I have found the importance of community, of empathy, of solidarity and the radical idea of love that is capable of transformation and justice.

4

5

It is natural to talk about Dr. Ambedkar while engaging in identity discourse and Dalit literature in the classroom; but even in other subjects or classes of literature, Dr. Ambedkar and his ideas speak to ideas of harmony of life, compassion, unity, which are also the foundation of our Constitution.

If you teach literature and sociology in class, then it is very natural to raise questions of gender and caste and Dr. Ambedkar helps us to look at these two questions together. Without seeing them together, understanding the caste structure and women’s issues in the Indian context cannot be possible.

6

7

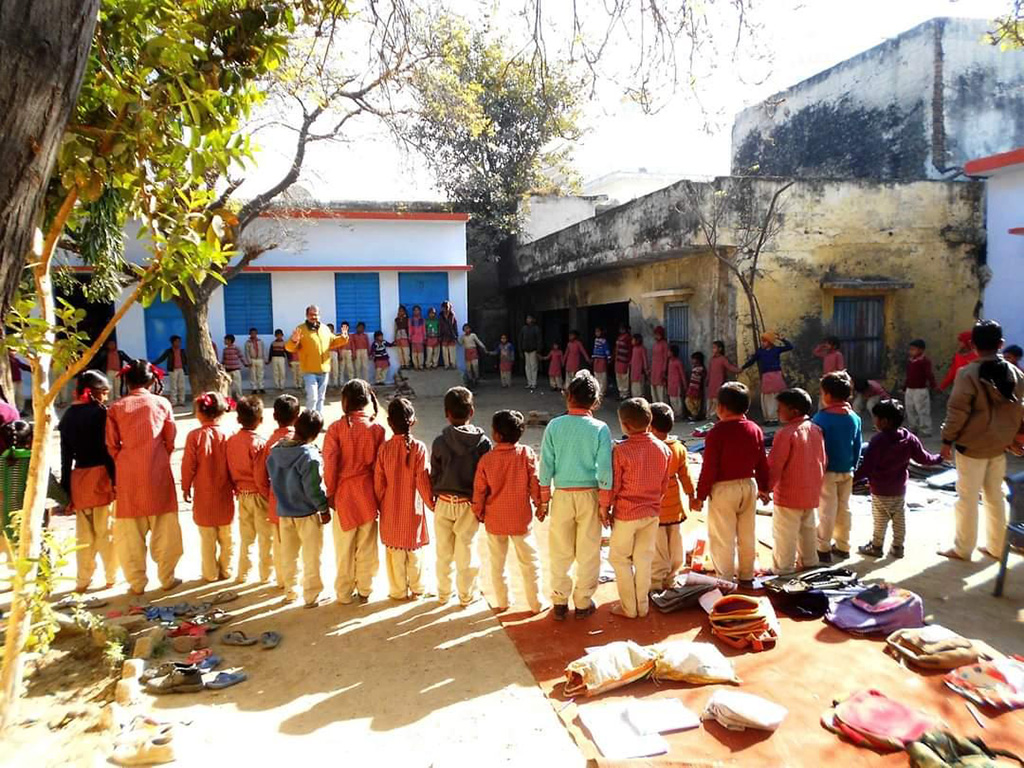

The meaning of Ambedkar’s existence is as important to me as it is for anyone who comes from a disadvantaged group. All aspects of his ideology can be talked about and drawn from but what he thinks about education, especially in the context of disadvantaged groups, is what inspires me the most. At the same time, when Babasaheb considers the education of women as the measure of progress of society, the meaning of women and Dalits’ existence extends far beyond the fight for only rights and entitlements.

Had it not been for Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar, perhaps I would not have been writing about him today. It is the result of all the social and human rights battles fought by him that innumerable people like me were able to move forward in the direction of attaining education and carving out a place for ourselves in society, hitherto denied to our ancestors.

8

9

10

Students from different social locations come to study at Ambedkar University. After reading Dr. Ambedkar’s books and engaging with his philosophy, I understood how important it is to be inclusive within the classroom.

It is the responsibility of a teacher to ensure that students from different castes, classes, genders, social backgrounds, ethnic backgrounds get an equal, just environment within the classroom and I think learning to do this is how Babasaheb has helped me the most.