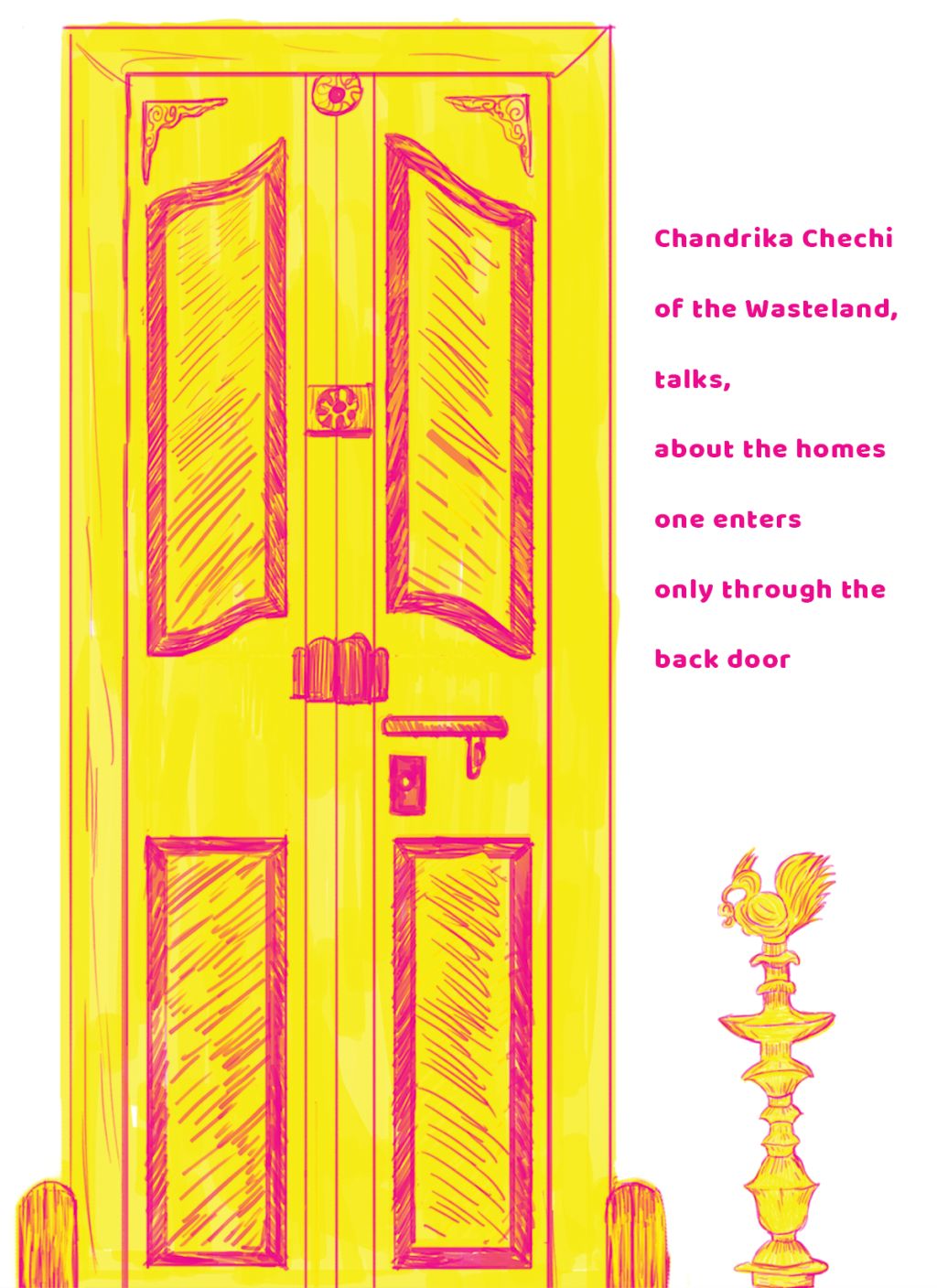

Poem by Vijila Chirappad

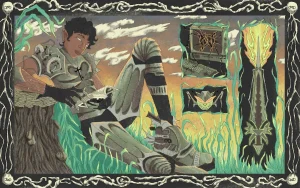

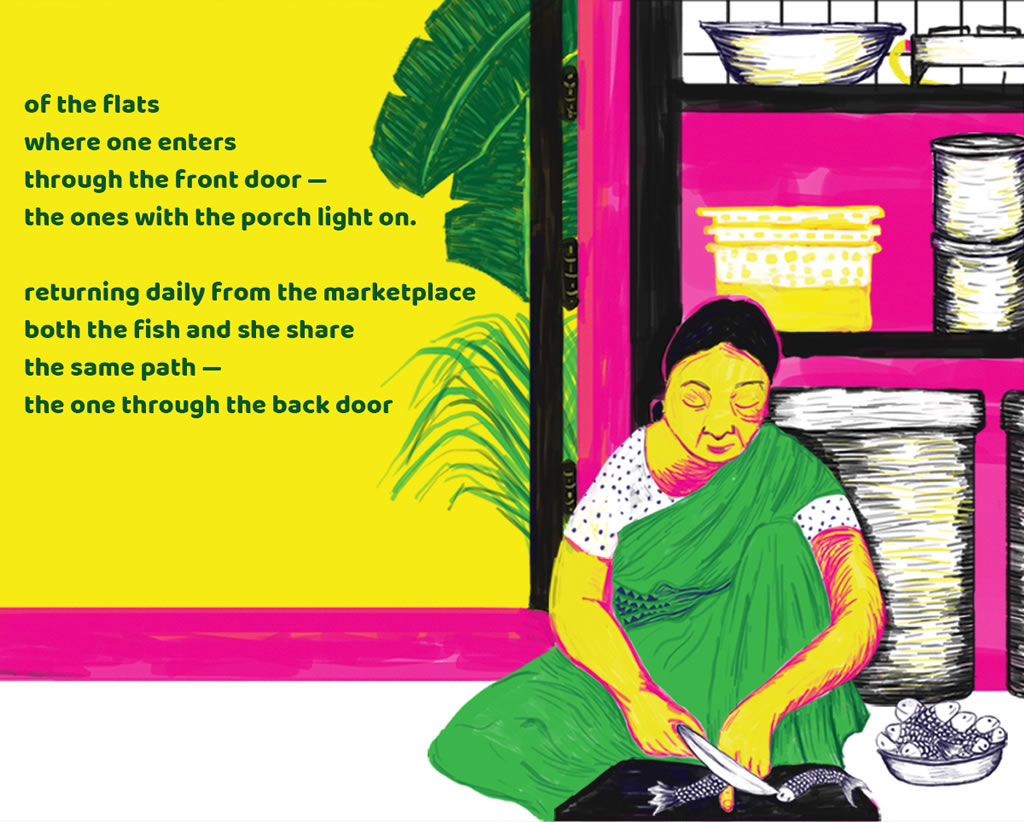

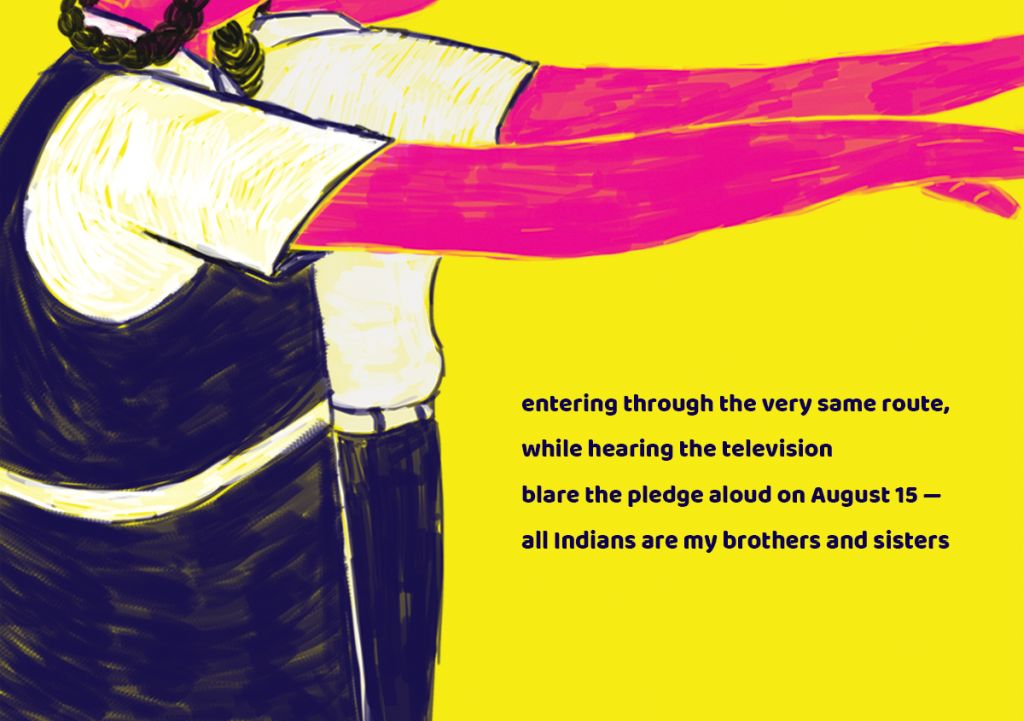

Art by Shrujana Niranjani Shridhar

The Third Eye introduces a new series inviting poets and artists to interpret each other’s worlds.

Vijila Chirappad is one of the freshest voices in Malayalam poetry. 39-year-old Chirappad’s poems are pithy and stark, and often light up common blind spots, such as the way caste plays out in Kerala’s communist history. Her experiences as a Dalit woman informs her short, witty poems as they look out at Kerala society.

Chirappad has always been a huge reader. “When I was in school I would read my older cousin’s college texts,” she says, laughing a little at the tiny prodigy she was. Chirappad is wry and honest, in her writing and even in casual conversation — whether she is talking about her two-hour bus rides to work from her home in Perambra or looking after her bed-ridden father or the many fans and friends who translate her work from Malayalam to English and other languages. Chirappad’s work is already part of a couple of college courses in Kerala and appears in several anthologies including the Oxford India Anthology of Malayalam Dalit Writing (2012).

Chirappad is an admirer of the works of the late Madhavikutty (aka Kamala Surayya), Satchidanandan and Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award winning S Joseph (author of My Sister’s Bible — another powerful critique of casteism in Kerala). Even within the powerful vein of contemporary Dalit poetry in Kerala, Chirappad stands out with her intimate, seemingly effortless exploration of women’s worlds.

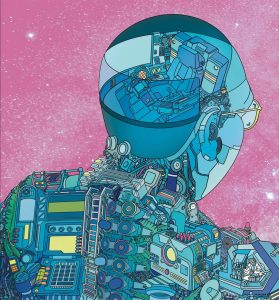

Shrujana, artist and co-founder of the Dalit Panther Archive, read Chirappad’s poem, Wasteland and this is what she saw.

Shrujana says, “I started working as an artist with storybooks. As a child, my interest in art also began with storybooks. I don’t think of myself as a Dalit artist per say, I’m a visual artist born into an inter-caste family (my father is from an SC community and my mother is from a Bahujan community) I work from an anti-caste and feminist perspective.

I have been working on a project on the Dalit Panther movement and the little magazines of Maharashtra. Since the research started, I have found myself thinking more and more about the Buddhist culture and history that the late poet, writer and artist Raja Dhale kept pushing us towards. I am asked about a Dalit ‘aesthetic’ but I don’t know what a Dalit aesthetic is, since Dalits aren’t a monolith. There must be thousands of different visual styles and cultures depending on the different Dalit communities specific to regions and languages across the subcontinent. Often, as folx from marginalised communities, we aren’t allowed to see ourselves in the history and legacy of this country, even though we are the artists and crafts persons behind all the ‘rich’ and ‘diverse’ Indian culture. But, I don’t think I represent a community or anything like that; I’m very aware of the space and perspective I function from, but I’m just one artist from a community of phenomenal artists and creators for centuries. I can only represent my experiences and hope that others can connect with it.

The art school I attended didn’t have any caste or class-consciousness and was dominated by people of extreme caste privilege. The only person I could connect with in that institution, who knew exactly what my struggles in building a practice is going to be, was Abhiyan Humane. He was a great teacher and although I never had a class with him, he was my guide. At the very beginning of my career, he set me up with internships, jobs. He knew just how intimidated I might be and ensured that I felt confident and comfortable in what I do. He taught me that I had a right to be there and exist as an artist.

Besides that, my parents are also from the movement, so I grew up around the best poets, writers, artists, translators. I knew of Namdeo Dhasal before I ever heard of any American poet in art school simply because that was my family’s world and it was a privilege.

In terms of visual art, I was struggling to find a space that I thought represented me or I felt safe in. And, although, I was never part of Clark House Initiative, contemporary artist Yogesh Barve invited the Dalit Panther Archive to participate in a group exhibition with them. But long before that, CHI and its artists were people I wanted to learn more from and be around. I think after I met the artists of CHI, I felt safe and understood in the ‘art world’ for the first time. That’s why spaces like these are important and should be encouraged, supported, and protected.

Vijila Chirappad’s poem, Wasteland, really stood out for me. Especially, the literal and notional back door in the poem. It captures the hypocrisy of dominant castes and their charades very eloquently.”

Vijila Chirappad‘s work includes three collections of poetry in Malayalam: Adukala Illathaa Veedu (A Home without a Kitchen, 2006), Amma Oru Kalpanika Kavitha Alla (Mother is not a Poetic Figment of our Imagination, 2009), and Pakarthi Ezhuthu Her poems “A Place for Me”, “Can’t Grow My Nails” and “The Autobiography of a Bitch” have also been included in the 2012 Oxford India Anthology of Malayalam Dalit Writing.

Shrujana Niranjani Shridhar is an illustrator and designer practising in Mumbai. She completed her Diploma in Visual Communication and Art from Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. In 2016, she co-founded the Dalit Panther Archive to document the Dalit Panther movement of the 1970s.