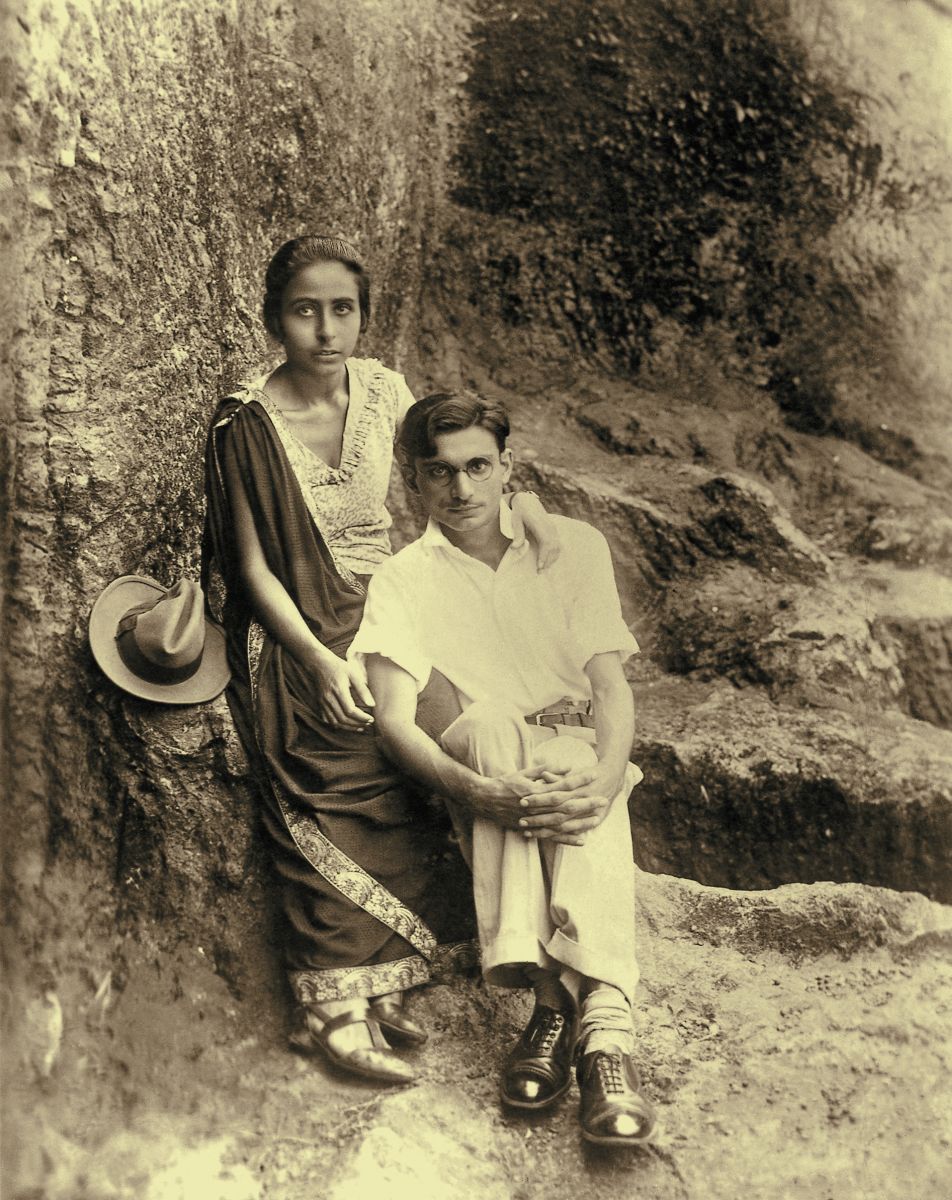

Sabeena met Homai to shoot her documentary Three Women and a Camera in 1997, and ended up uncovering a feminist history of Indian nation building rarely seen, never heard, and lovingly told in the Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla. “Homai lived a quiet retired life for 23 years and she took all the success in the same philosophical way as she took the anonymity,” says Sabeena, eight years after Homai’s passing. “The film was only the beginning of a long association with Homai. We wrote letters to each other, I would travel to Baroda every few month to look at her photographs and to try and understand the person behind these images. To annotate her archive with her rich experiences that spanned almost a century of Indian history. Her memory was razor sharp and it needed little jogging to set her recounting stories and anecdotes. As our friendship grew over the years, I realized that she was an extraordinary woman who lived an entirely self-reliant life. She built her own furniture, stitched her own clothes, did electrical and plumbing repairs and created nifty house-hold gadgets. She often said she was like Robinson Crusoe. Her island was her home in Baroda where she lived independently till the last, with her plants and a few personal photographs.”

The Third Eye presents Homai Vyarawalla’s singular view on women and work, historically and personally, as narrated by Sabeena Gadhioke.

I will tell you a funny story. I had to cover a big function at Rashtrapati Bhawan, so I made a blouse for myself. I hand stitched the sleeves with ordinary thread but forgot to put them through the machine. While shooting the banquet hall, I raised my arms to take a top angle view and found the stitches giving way! One or two ladies sitting there even saw me and started to laugh. You know what I did? I pulled out the sleeve that had come off, pulled out the other too put them in my bag and started working again.

1

2

“We moved from house to house in Bombay depending on our financial situation…five of us lived in one room. We had a our kitchen and bathing space in the same room…When the rents got too high, we shifted to Andheri and I would catch the 6.30 am train to Grant Road for school. I had to complete most of my housework before that because my mother suffered from chronic asthma. My brother and I fetched water from a well from the fire temple compound and we had to climb up a hillside to go to the toilet…Initially, we didn’t even have an almirah and lived like hermits with trunks and folding beds. It was only later, when both Maneckshaw and I were earning, that we were able to furnish the house gradually.” Homai Vyarawalla in Camera Chronicles.

3

4

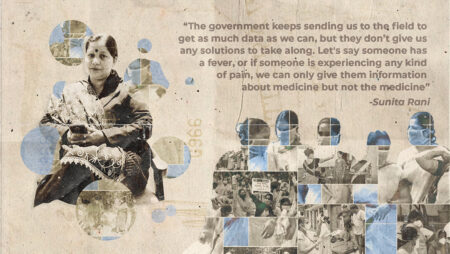

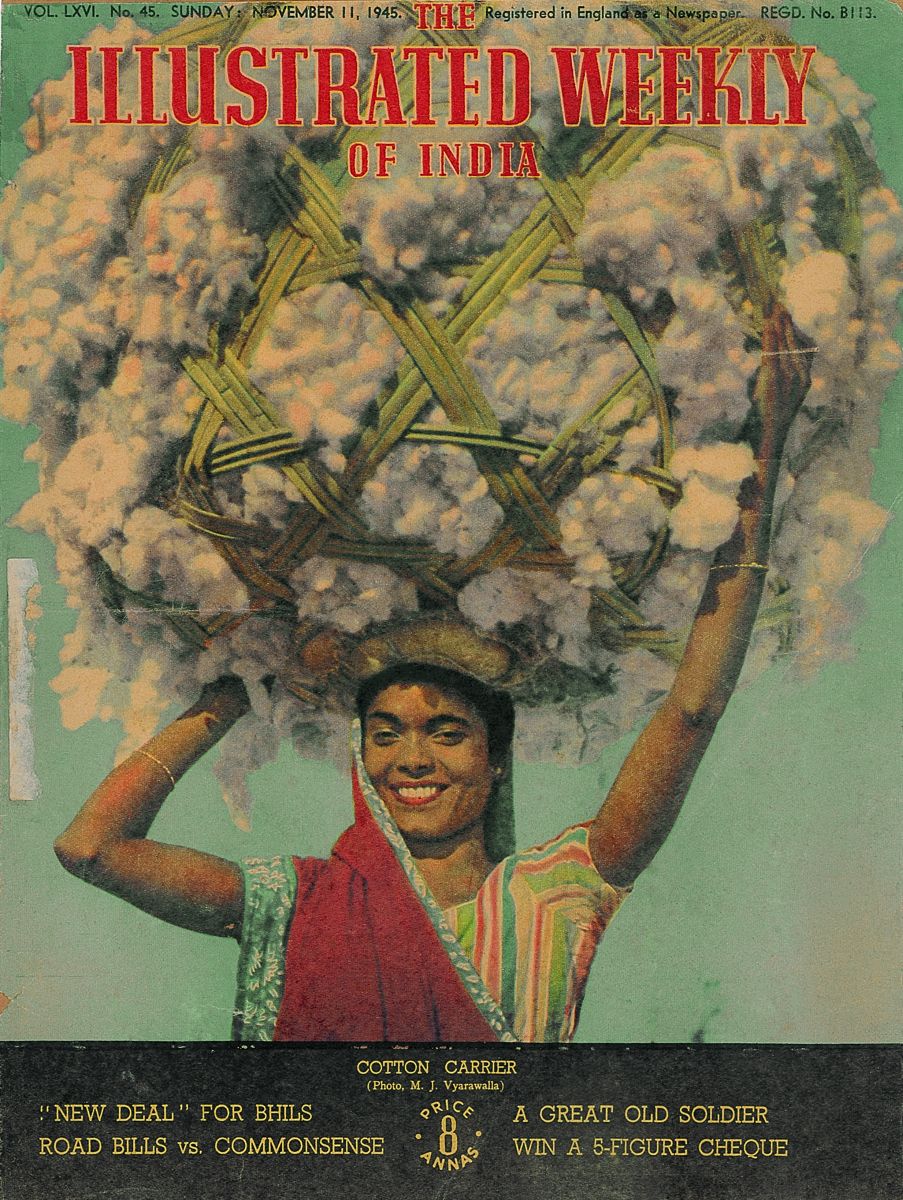

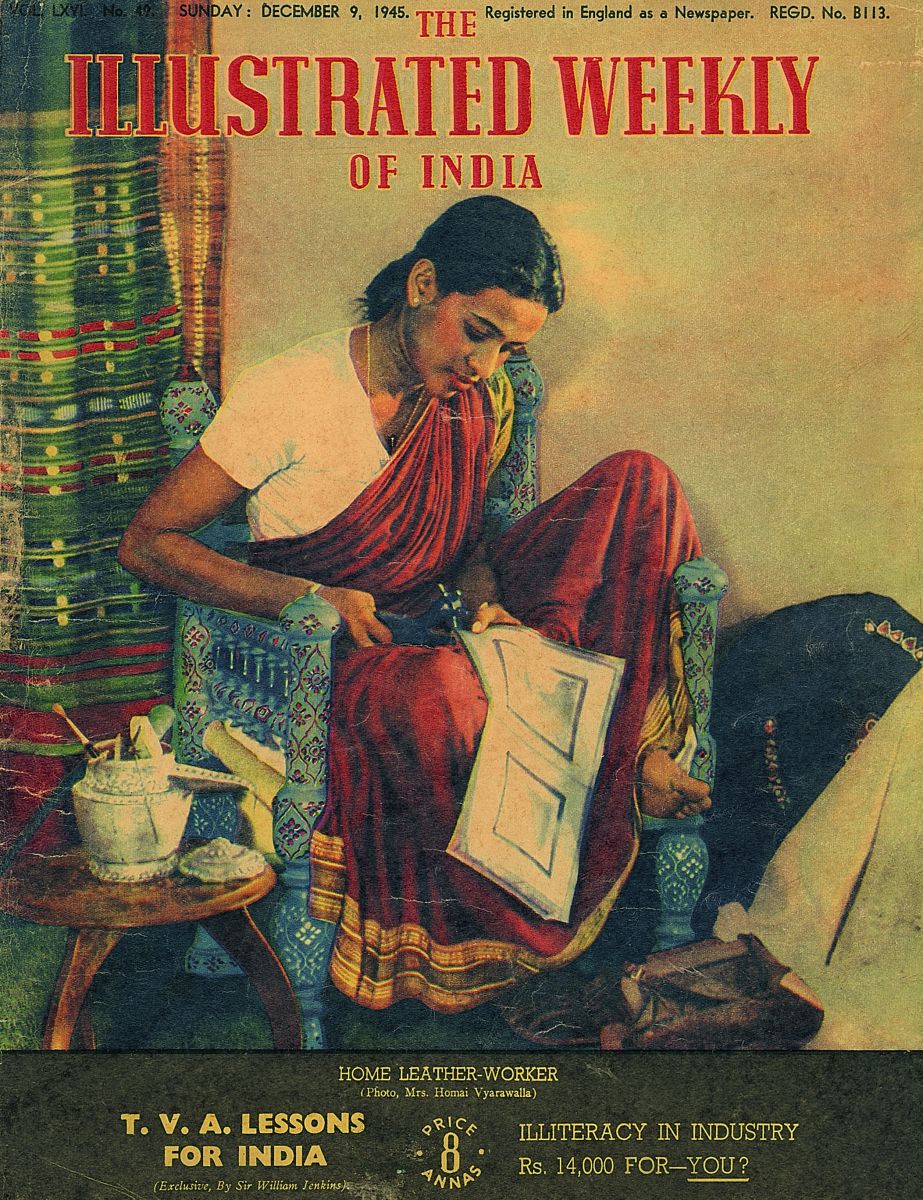

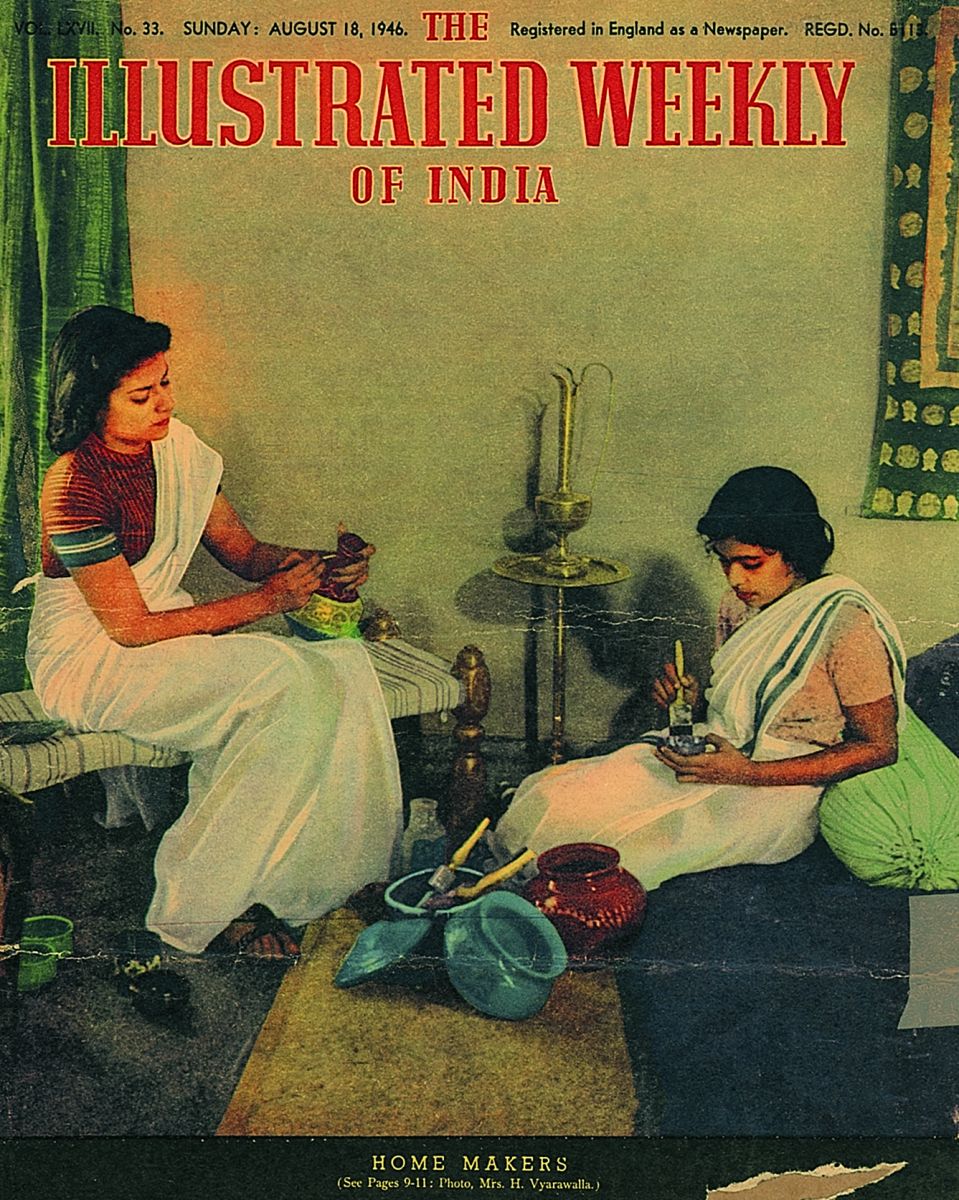

“Women appear as homemakers as well as participants in public life in Homai’s early images, presenting more complicated insights into gender relations and acceptable roles for them at the time. An article titled “Careers for Indian Women” in the Illustrated Weekly of India dated May 11, 1941, describes the women’s education to be “the companion and inspiring helpmate of her husband” and most professions were placed as pastimes that would aid their role as homemakers. The discipline of Home Science (some of these images were taken later at the Lady Irwin College in Delhi, 1946), was also grooming women to be more efficient homemakers. …Some of Homai’s images of women in Bombay seem also to suggest that there were new options opening up for them like architecture, window dressing and advertising. Predictably, these were highlighted in the “Home Section” of the magazine,” says Sabeena Gadhioke in Camera Chronicles.

5

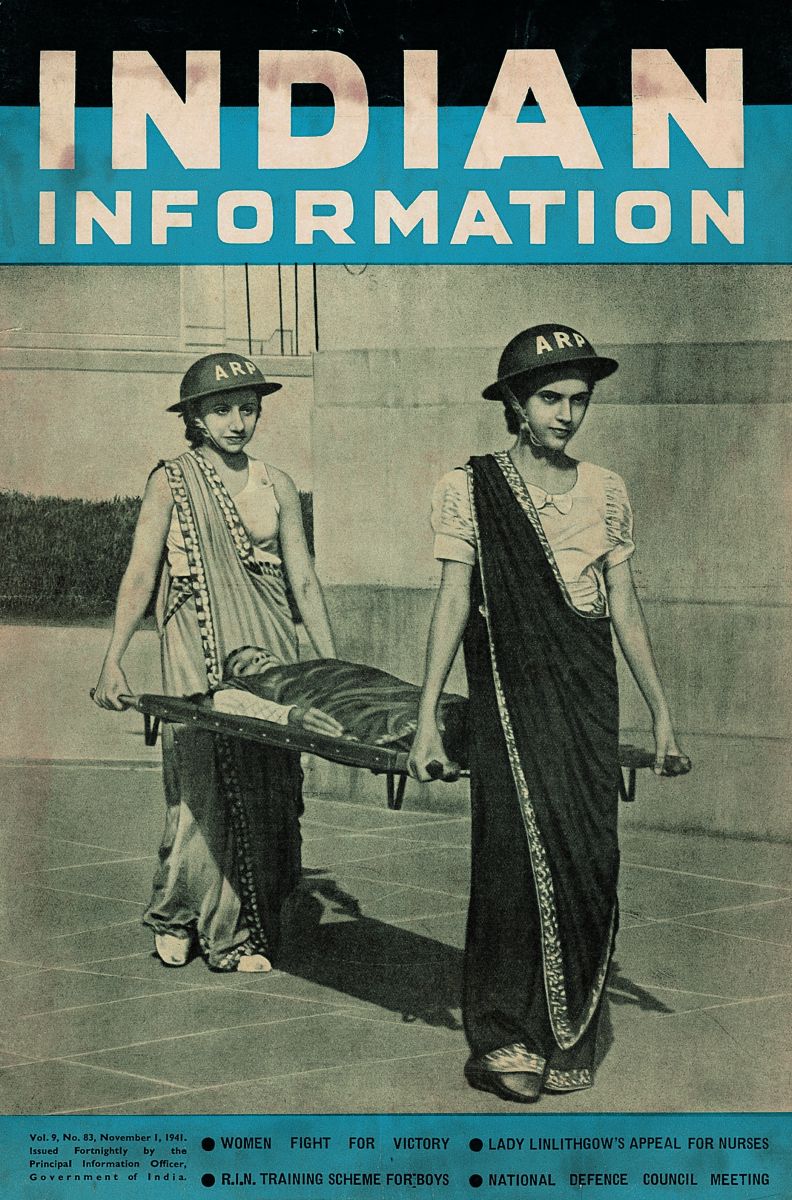

“Prominent amongst her early spreads are images of Parsi women being trained for rescue activities in Bombay under the British rule in 1941. The demands of the Second World War were urging some women out of the home…this move into the public domain was probably in keeping with the peculiar conditions of a war that had created new spaces where women were needed,” says Sabeena Gadhioke in Camera Chronicles. Today, she continues, “The Parsis of Bombay were quite deeply involved in what was called the ‘war effort’ by Homai: Developmental work that would support the agenda of the British during World War II. With the exception of a few, most Indian leaders and, notably, Gandhi, asked Indians to support the British state. What you see in Homai’s pictures are staged vignettes of women learning basic Air Aid Precaution skills. As women of the same age, these subjects were often known to her. Some were her friends. In Calcutta, an elderly lady once came up to us at a show and pointed to herself in one of those photographs.”

6

7

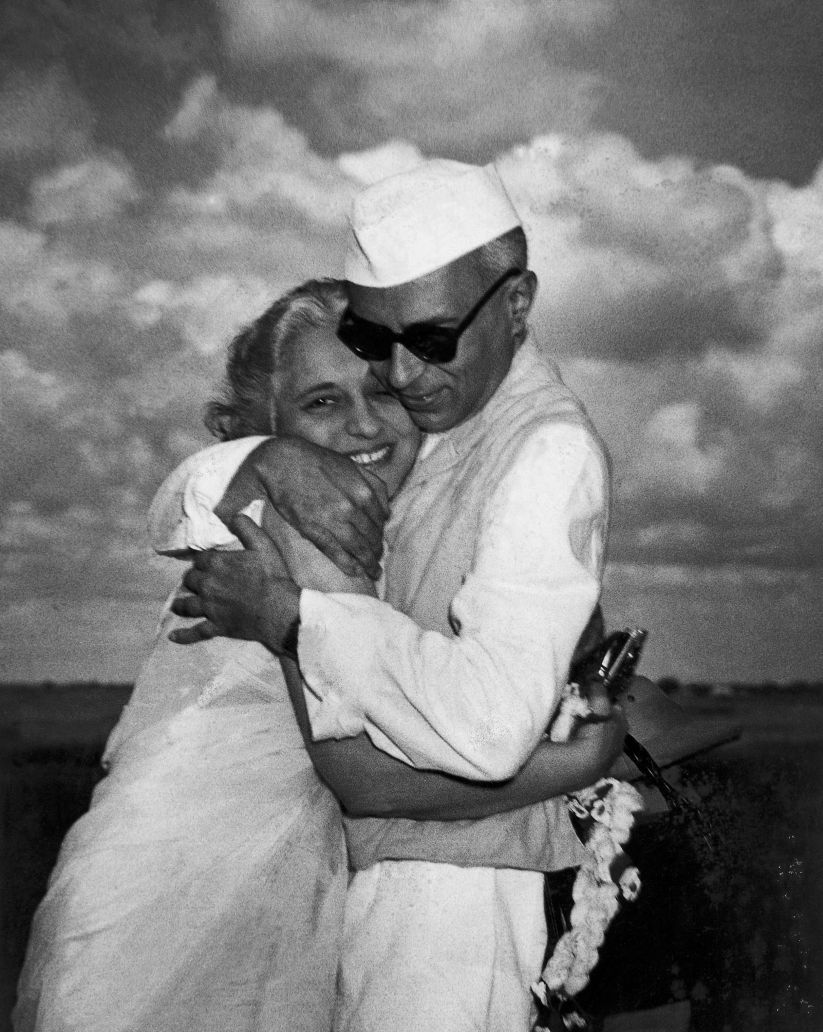

“Gandhi did not enjoy being before Homai’s camera sometimes, as he hated the flash. It was in death that Gandhi, whom she admired greatly, was to be photographed most by her. On the 30th of January 1948, Homai was to cover the Mahatma’s prayer meeting at Birla House. Armed with a colour movie camera, she had just stepped out of the office when Maneckshaw [husband] called her back. He said that he would accompany her the next day with the still camera. This decision was to cost them dearly. “Within a few minutes he returned with all the blood drained from his face. I said, ‘What has happened?’ He replied, ‘Gandhiji has been assassinated!’…It was possibly the most important picture that she had missed in her life…” says Sabeena Gadhioke in Camera Chronicles.

8

“In some ways Homai had a lonely presence as the only woman among so many men: a press photographer in the arena of national politics, also dominated by men. She had to occupy a ‘man’s world’ in order to survive but she did that on her own terms. She wore a sari but was non fussy and smart and not overly ‘feminine.’ She did not take any nonsense from anyone. But her profession and the demands of home also meant that she had little time to socialize beyond the family.

She once admitted that women scared her a bit with their talk of jewellery and clothes and make up. In 1969, Homai’s partner Maneckshaw passed on suddenly and she gave up work finally to join her son in Pilani. This is the first time that Homai had time to interact with women and she learnt to trust and make friends. She made some of her closest women friends here. And she did ‘womanly ‘ things that she had never found time for like organising shows and plays and baking and flower arrangement competitions. She often said that this was another phase of her life,” says Sabeena Gadhioke.

9

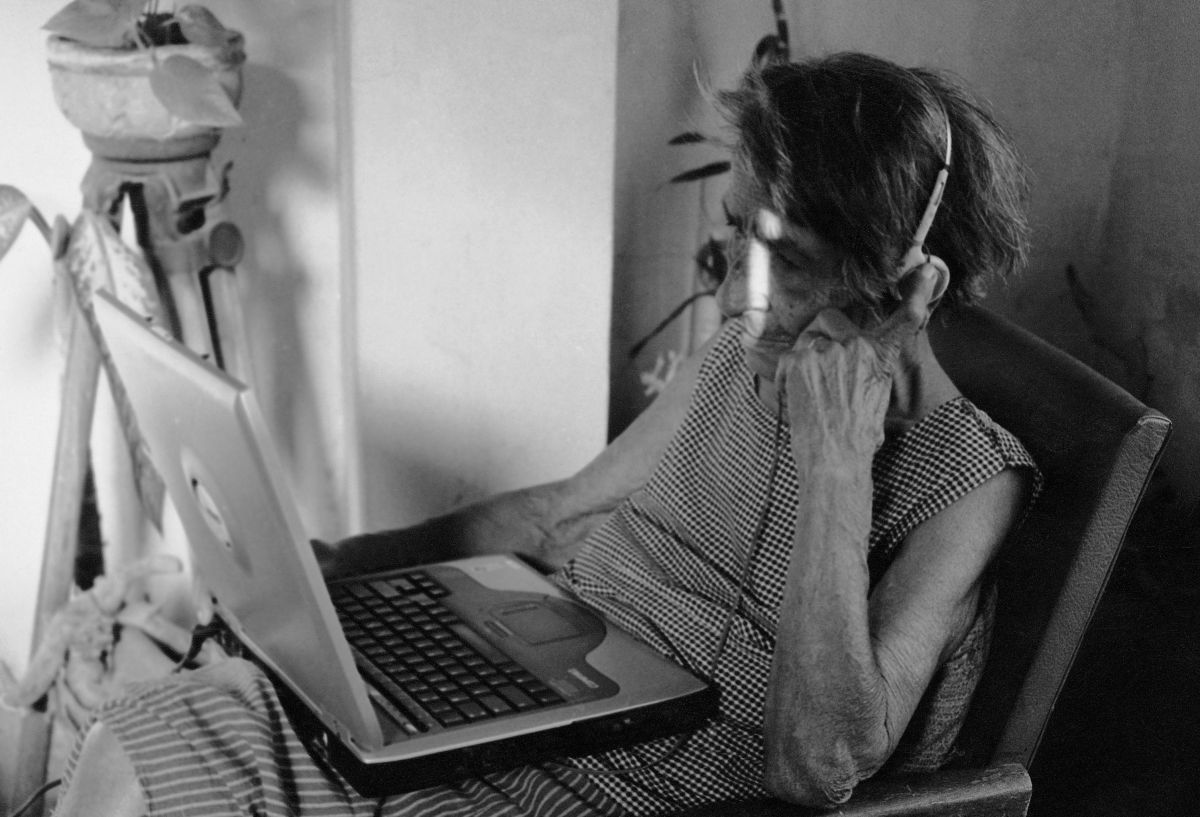

The book Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla released in 2006. This was followed by a retrospective exhibition of her work at the NGMA in three Indian cities in 2010 and 2011. “In each venue, Homai Vyarawalla travelled for the shows and personally supervised the hanging of the photographs. What was interesting about the shows was that it re-introduced Homai to some of her own work – work that she had not viewed for over a half a century. As the exhibition travelled from Delhi to Bombay and then to Bangalore, the space given to what Homai called her “important pictures” – photographs of iconic moments of nation building and their architects –shrunk, and the portraits of everyday life and ordinary moments captured by her camera took precedence. When we returned from the last of these shows there was a request waiting for Homai from the curator of the Rubin Museum in New York. Would she be willing to travel to New York in July? The answer that she sent me on SMS read, “Dear Sabeena, so sorry for late reply. Yes to New York trip if they arrange for both of us. Life is getting to be more difficult with passing days. Would love to escape. Warm hug.” In her nineties, Homai Vyarawalla had learnt how to use a mobile phone. In 2008 at the age of 96, Homai travelled across the Atlantic making her first ever journey abroad. December 9, 2011 was Homai’s ninety eighth birthday. It was the first time that I was visiting her on her birthday and it will remain one of the loveliest days that I spent with her. The next day she spoke about a disobedient and ailing body that she described as a ‘broken house’. The person who lived within it, she said was still young. A month later she was gone but I carry forward the memory of the truly extraordinary and forever young Homai Vyarawalla that I knew.”

10

By age 92, Homai had lived on her own for the last sixteen years. “She says her life has come full circle and calls herself a “bachelor girl”…Homai manages everything on her own. She cooks, cleans, drives, shops and creates wonderful things with her hands. She is also a carpenter, plumber, electrician, architect and general handyperson. In all these skills she is her own inventor and, designer and collector of things. Homai ‘Kabadiwala’ as she calls herself, never throws anything of use…Most objects and furniture in her house have been fashioned by her. She makes her own clothes, repairs her own slippers and cuts her own hair. She can upholster sofas, paint walls and make furniture…” There has never been one boring moment in my life. I’ve never said to myself, ‘I’m bored.’ If I have nothing to read, I start reading the paper in which groceries are tied.”

All photographs featured in Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla by Sabeena Gadhioke, published by Parzor Foundation and Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.

Photographs courtesy: HV Archive/ The Alkazi Collection of Photography