Prof. Milind Sohoni teaches at the Centre for Technology Alternatives for Rural Areas and Computer Science and Engineering Department at IIT Bombay, and has been advocating the development of vernacular science—as an idea and pedagogy—in the way our schools and universities approach science education. Challenging the big science hegemony (“stem cells, nanotechnology and the poster boy, machine intelligence”), Prof. Sohoni asks, whom does big science deliver to? Deeply involved with finding local, regional and people led solutions to actual on-ground problems (“the chulha is not just a cultural object, but a scientific object”), The Third Eye explores the role of science education in our expectations of public health, and how, as we turn into consumers of science rather than producers, we forget that science has stopped serving those that need it most.

As a science educator, what was your reaction to the so-called vaccine hesitancy in the country?

I would like to not collapse the two: scientific temperament and vaccine hesitancy. But I do think that science education has failed us in a big way.

First, about the vaccine hesitancy; I think people made rational choices. In the first wave there were very few deaths, so people did not see the need for the vaccine, especially for those without comorbidities. But the second wave came, and the hesitancy disappeared quite fast. So, it’s a very rational hesitancy: “Do I need it?” And once they saw that the second wave was killing people, sure enough, people lined up.

But why I say science education has failed us is because of the way we failed to calculate the human cost of the [Covid] pandemic.

I studied in a Central School [now Kendriya Vidyalayas] and Central School textbooks are very good. But by classes 11 and 12, they are focussing on competitive exams or this national education. Instead, I wish the textbooks had exercises like let’s visit a bus depot, or let’s visit a good farmer and find out what the yields are, or let’s visit the PHC sub-centre, talk to the nurse, talk to the compounder, talk to the two doctors, just getting familiar with the PHC (primary health centre) as something which provides a critical health service would have helped a lot. Or spend time with an ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) worker. She has a notepad with names of people in a village and the diseases they have, which family has what medical emergency. How is it X village has so much diabetes and Y village has none?

So, I think it’s a bigger awareness, which science education has not built.

Are you saying science should speak to contexts?

I am saying that science education is not just about big science, and should not be about big science.

But if you look at the main central government departments populated by scientists, they are Space, Atomic Energy and Defence.

Okay, so we have missile men and women, big people in science, but really, so much of science in most of the developed world is really sadak, bijli, pani.

You know, even MIT, till 1956, had a Department of Sanitation Engineering. And in 1956 they thought that, well, Massachusetts has had good sewers for long, we don’t need any more research in it. So, I think, the material problems of that particular society have to be posed, “Why does my well get dry?” or “Why does my bus come late?” I think more than the subject matter of science, which may be universal, the methods of science are very cultural.

In Mumbai University, we have been working on a case study. We go to villages and we study—for a village of say, 1000 hectares, how much rice is grown? How much comes from PDS (Public Distribution System)? How much is sold? So, the mass balance of rice is calculated. This has found many interested students because they suddenly understand what is the relationship between yield and poverty or export and health.

Or we go and ask, “Which is the best chulha in the village?” And that's astounded a lot of students; :Is chulha a scientific object?”, they ask. And I say, “How do you call a chulha good or bad?” Often, girls respond fast. They say, “Well, it should be faster,” or "It should have less smoke,” or “It should consume less wood…”

So, I think this sort of probing, documenting, doing fieldwork, establishing causation—these are really important parts of science. The subject matter maybe atomic energy, or “Why is the bus late?” or measuring fever, and so on.

Do our scientific institutes also need to reflect on their place within society?

Most definitely. For example, if IITs get analysed, how many higher caste students and how many SC/STs students are there really? And to add to that, what are IITs doing about caste realities?

You are also talking about making social sciences and physical science talk to each other?

Absolutely. You know, this dichotomy of social science and physical science is a mutual, I think fear, or I don’t know what. So engineers will say you need so many kilos of food per year, or if I weigh your child in front of you, and the child is only six kilos, or ten kilos, and the child is 10 years of age, there is a problem. But that cannot be the only way we understand child malnourishment, right?

In most other nations such division is not there. And I really think that social scientists should start looking at us engineers, and we also should start looking at social scientists with much more interest, much more critically.

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers Act came long ago, and along with it came a list of 42 [pieces of] equipment, which every municipality should have; a mask, a jetting machine, pumps and so on. Now, even IIT campuses don’t have that equipment.

Is there any lab that has a ‘test mask’ even? Our men are going into tanks and dying because of [lethal] fumes. A ‘test mask’ is an investment. You need a face-like structure and an artificial lung exposed to various environments to test its efficacy. And this mask needs to be standard equipment in every state.

But these are things we never asked IITs to do, right? We never asked, “What problems bother society? What do people need?”

So, I think social scientists need to look at physical scientists very carefully. And on the other hand, physical scientists also need to look at social scientists very carefully.

So, what would you say is the way forward for science in the Indian context?

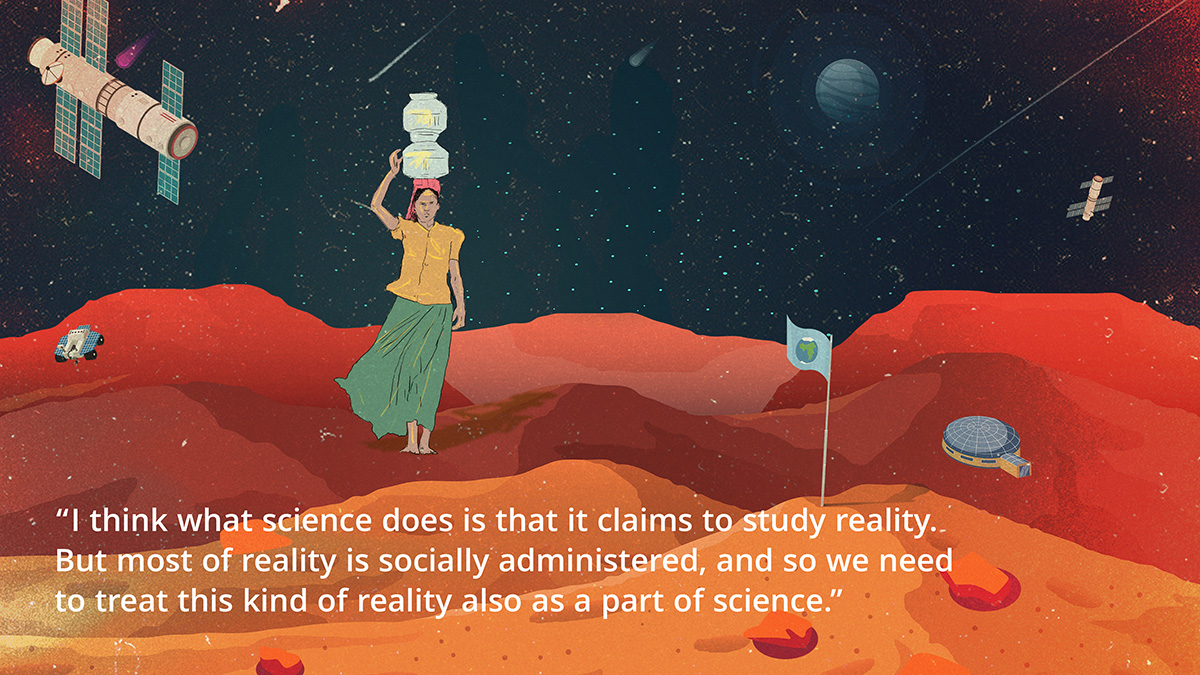

I gave a TEDx talk in IIT Bombay on what we call vernacular science. If you look at vernacular architecture, it is something that is functional. Similarly, vernacular science is about the delivery of material answers.

I think what science does is that it claims to study reality. But most of reality is socially administered, and so we need to treat this kind of reality also as a part of science.

Vernacular science looks at immediate material questions and tries to apply the methods of science to that. Material questions like, “Why did the well dry up? What was the system of extraction of layers to dig the well?”

So it’s really a science that worries about the delivery of all of these real-life questions. You should know that if you buy cornflakes, and it comes from Kanpur, what are the social and economic conditions that made Kanpur the manufacturing hub and why not where you live? So what this vernacular word is really saying science should be more of functional. An interesting example is a student had knee injury, and he was hurting, and he got an MRI and doctor suggested an operation. But did he just say okay? No. He relied on an uncle’s advice on whether to do it or not.

So, I think even the consumption of science needs a cultural third party to make it acceptable; otherwise, it’s not going to be acceptable.

There is a rising argument for medical pluralism, one that integrates local health knowledge systems into the public health paradigm. Is this something that pure science could be ready for?

Whether a kaadha (homemade medicinal decoction) works (which I take), or tulsi prevents congestion (which also I take), from a ‘scientific’ point of view is an unnecessary dichotomy, I feel. If it works, it works.

Let me just rewind: I think there are two parts to science. One is whether something works; then the second thing is whether we know the reason why it works. This separation of whether it works or not, from whether we can explain, is a very important step, which even Western science took a long time to understand.

For example, in the 1800s, one particular surgeon in Europe noticed that washing hands [before surgery] actually helped reduce mortality, but he had no explanation for it. And the senior surgeons pooh-poohed it and said that’s not true. But then, after some 30-40 years, bacteria were discovered, and they found that actually [he was right].

So, scientists also have to accept that there are many things that we don't know, and it’s still holds true. Scientists work empirically and sometimes we say okay, let’s park it, carry on, and maybe later on we will find out the ‘why’.

The ‘why’ or the explanation is very cultural.

How do I explain a body is quite different for different people or for different cultures. For example, in Japan, when they point to the self or ‘me’, they always point to the nose because they think that my breath is me. While Indians point to their heart when they say ‘mein’…

So… if it works, it works. Just accept if it works, and we should document [pluralistic health ideas].

Do you think that the way that our science, and particularly technology, has progressed, science education is tilting towards more technologies that are serving Big Business and corporate profits, rather than this developmental model of really looking critically at society?

Yes, I think so.

I think that these material questions are no longer the motivators of science. I mean, it’s so unfashionable to say these things; you are lumped as Gandhian (you know, which I hardly am). These brass tacks are going out of fashion.

But science today gives something else. Longevity of life, for example. Science has convinced us, and is delivering on its promise of making us live longer. Whether those extra five years are of higher quality is not under discussion. You know, this is the same as people coming from really nice places in the Konkan to a slum in in Mumbai and staying there because they want certainty. Life in rural Maharashtra is very hard. There’s more certainty if I’m a peon or a security guard in the city.

I think that science is really offering some ‘certainty’. And that is what we seem to have accepted. And that certainty is coming from many of these scientific things, which we don’t understand, and which are delivered by Big Science.

Big Technology has a knack of turning us all into consumers of science, by neutralising questions on ‘how’ and ‘why’ things work. We accept it and we enjoy the benefits. But see, if you know the benefits are divided very unevenly, why doesn’t it bother us?

For example, if you buy an Apple iPhone for Rs. 75,000 how much does the actual makers of the phone (factory workers) get? I call it the Buddhufication Crisis; a lot of people are just hooked on to their smartphones, and live in a bubble of manufactured certainty; and the rest of society that can’t access smartphones, is left to deal with real-world problems.

Tell us more about this Buddhufication Crisis.

I am a birdwatcher, and if you look at the wild, if you look at the jungle, if animals were as ignorant about the way things worked, they would be dead meat. Can you imagine a deer that can’t judge how close the tiger is? It will be eaten. But we human beings seem to sustain such stupidity in ourselves. So we are living longer, we are still shitting on the road or, you know, letting our sewage be cleaned by fellow humans at the risk of death, but we are living longer. And that is, I think, a big problem.

So, these are the two or three things, which are learnings for me. And I think that the role of culture and sustainability is really important.

Science can offer us certainty, you said. What is the relationship between science and desire?

I think real life is full of uncertainty and the German efficiency or the First World’s bus coming at 3.07 pm every time is aspirational because we all desire certainty. It’s a human trait. And that is the weakness big science is really exploiting.

We are no longer a risk society; we are a desire society.

Through our Public Health edition, we also seem to sit with the feeling that science is not serving rural areas, not serving the poor. In turn, there is also a lower expectation of science from the rural communities. Do you feel this is true?

Yes, I think that is true to a large extent. But it’s not to do with rural. You see, for example, if you look at western Maharashtra—the Pune-Nashik belt—some of the cleverest people live there. They are basically producing vegetables for the urban big markets; in Satara, Sangli, that entire irrigated area. And in fact, you will see that they are very careful about their future, and understand their place in society and the role of the state. And they expect many things from the state or the government; they want things to work, hospitals to work, have oxygen, etc. And so, it is really about the basic understanding of cause and effect of citizenship. They understand what is needed to make buses work, or hospitals function; they understand how the state works. This is not very different from knowing how gadgets work.

So, understanding how citizenship works is also the agenda of science. Once that happens, rural people will demand better service and they will get it.

The hard task of a famer involves him being a chemical engineer, an irrigation engineer, and an economist. So what he’s expecting from science are ideas to make his daily work life better. Most people who are working hard are not buddhu. But they still need to understand how the state works.

But one thing which is very peculiar to India, if you look at IITs, or if you look at higher education from the British times, it was about exiting the current world. So if you you’re in a village, and you did well in school, you go to the taluka place, then you go to Bombay, do well there, and you go to New York, right?

So, it’s not really about has he really improved the village or the town, or he was the chief engineer who really designed the Nanded highway system or Nanded city… and that really made a difference. It’s about where did this bright scientist leave and go to!

So, our science is really an exit science and not about how things work or do not work, or why are buses late and can that be improved where I am…

IITs are really, mainly, lifeboats or escape hatches into the global economy.

So, our science is really a passport science on how to escape... and not improve the place where I am right now.

So, coming back to your question, I think it’s also related to how we perceive science.

Science is a way of giving agency to people, and not benefits. We don’t want to be made beneficiaries; we want to be agents of change, and agents of examining culture, enjoyment and so on. And that’s the only view of sustainability.