What does it mean to inherit a history of being both hyper-visible and unseen—of being watched, marked, and criminalized, yet denied recognition, rights, and voice? And what does it mean to make sense of this intricate legacy as a third-generation descendant, living in the present, occupying that complex and painful space between invisibilization and surveillance?

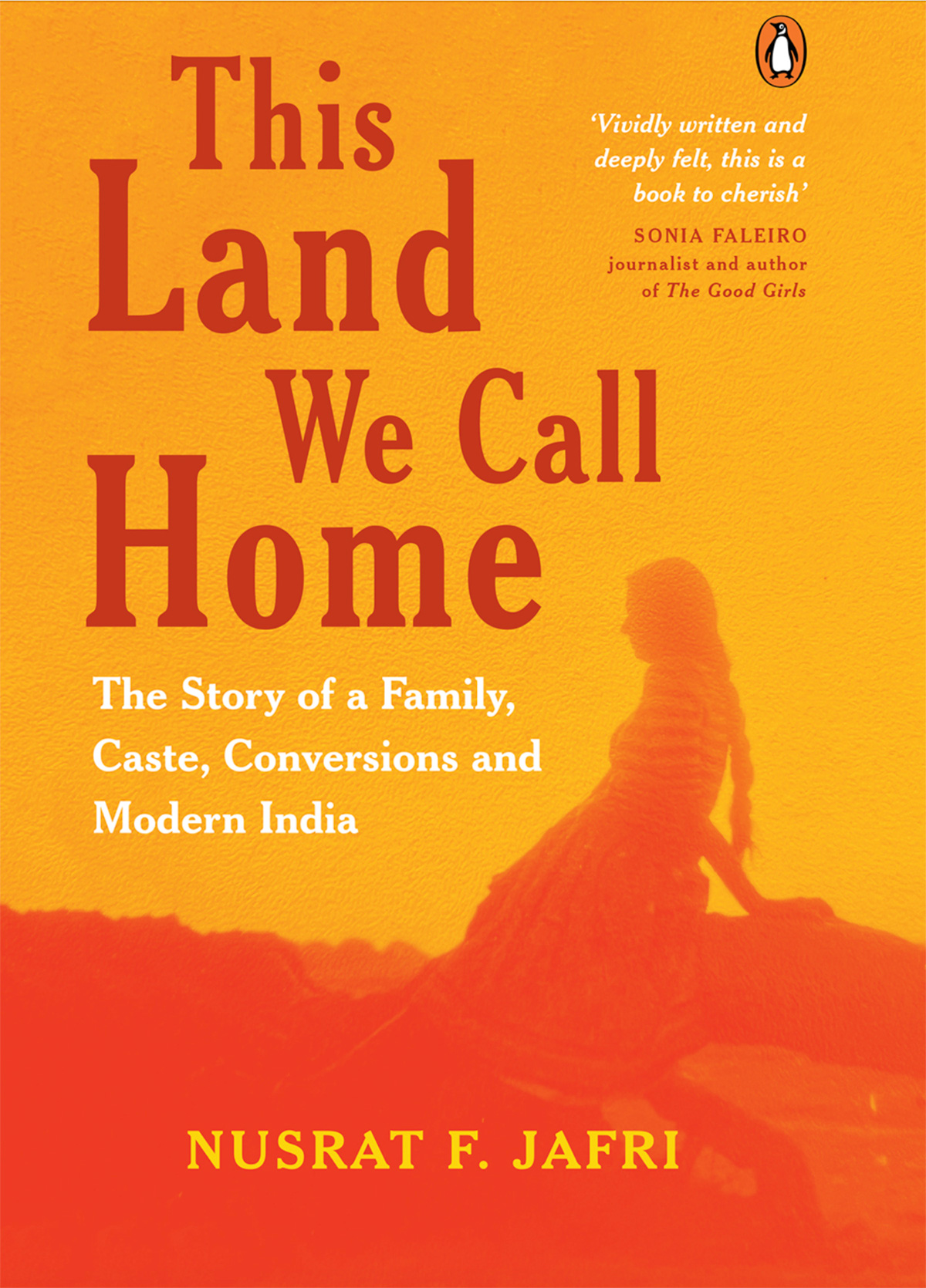

As part of our Crime edition, which explores feminist ways of interrogating crime and criminality, we share excerpts from Nusrat F. Jafri’s The Land We Call Home. In this haunting and intimate memoir, Jafri interrogates the colonial and casteist invention of hereditary criminality—through the prism of her own family’s history and the Bhantu Samaj.

She traces the life of her grandfather, Hardayal Singh, who was born into the Bhantu community, a tribe notified as criminal under the British Raj. Jafri shows how the Bhantu, like many other nomadic and denotified tribes, came to be perceived as collectively suspect—not through actions, but through the layered machinery of caste, social exclusion, and colonial law in India.

This memoir is not only a searing indictment of systemic injustice and colonial laws i India, but also a tribute to resilience. Through palmistry, prayer, storytelling, education, and spiritual resistance, Jafri restores dignity to a marginalised community that history tried to write out. In retracing the steps of her foremothers, she also reconstructs a world of pastoral life, belief, memory, and quiet defiance—a feminist act of remembrance and reclamation.

Do read it as a companion piece to Law and (Brahmanical) Order, a conversation on caste, carcerality, and policing in the Indian criminal justice system with Tasveer Parmar and Nikita Sonavane.

Hardayal Singh grew up in Bhantu camps, never staying at a place for more than six months. A camp would consist of around ten families, with a tribal panchayat or a leader to oversee their affairs. They kept cattle and sheep and were mostly herdsmen. Women in the community practised palmistry and sold handmade charms that were believed to possess healing properties or could ward off hostile spirits. The men and women of the Bhantu community displayed their craftsmanship by making reed mats and baskets from palm leaves and cane.

The Bhantu people were notably superstitious. They revered their ancestors through prayer and partook in pathar puja, a ritual involving the veneration of stones. Their altar comprised a brass plate with a triangular stone placed upon a crimson fabric. It was an unwritten rule that truthfulness was imperative when addressing the stone deity, and making deceitful oaths was strictly prohibited.

When these nomadic groups got weary or when the weather turned bad, they would try to set up temporary camps. But before they could do that, they had to inform the nearest police station and get a written permission. These camps were mandated to be at least three kilometres on the outskirts of the nearest village. Bhantus were treated like outcasts, and in the absence of many opportunities, theft and petty thieving was prevalent in the community. Despite this, they lived in a close-knit colony, where every activity of the group was directed towards achieving common economic gains.

Bhantu camps were nameless. As they were not a part of the main village and remained at their periphery, the camps remained unmarked and were denied the dignity that comes with formal appellation. Despite my earnest efforts to trace my great grandfather’s last whereabouts in Rajasthan, my aunts and uncles failed to recall the name, because as I later comprehended, a name had never existed. According to my mother, it was a quaint village situated in Alwar, near Delhi. Another aunt vaguely suggested that it could be a village on the outskirts of Bilaspur in Alwar. I meticulously combed through Rajputana for Bilaspur in an old Letts’s map of India from the 1900s, and was relieved to locate one there (as almost every state from north to central India has a Bilaspur).

Questions of whether all members of these notified tribes were indeed criminals perturbed me. I wondered whether the notion of hereditary thieves and congenital criminals was an Orientalist stereotype. But then caste-wise enumeration of the population was ‘already used by Indian rulers in the late seventeenth century, over two hundred years before the first British census report’. The discrimination was perhaps the ugly consequence of the already staunch caste system of the Hindu society… The 1871 Criminal Tribes Act didn’t clearly state which actions were considered criminal, nor how exactly crime was handed down through the generations.

—

Doctors and criminal anthropologists in the West studied the physiological and psychological traits of ‘criminals’. The belief that there was a generational transmission of criminal occupations that led to the emphasis on inherited characteristics coincided with Darwinian theorists of the nineteenth century.

—

My grandfather Hardayal and his tribe were not criminals even if they were so branded. They were, in fact, pastoralists. However, their Bhantu identity preceded them before they set foot on the periphery of a village, leading to discrimination and marginalisation fuelled by rumours and biases.

—

Despite the challenges they faced, both Hardayal and his sister managed to attend primary school. They became fluent in reading and writing Urdu and even acquired some proficiency in English. Their access to education opened new possibilities for them, providing a glimmer of hope for a better future that diverged from the hardships faced by their ancestors.

—

Among the many restrictions imposed on men of his tribe, riding bicycles was strictly forbidden, but a courageous few defied these norms. Hardayal’s father owned a rusty second-hand bicycle. But since bicycles couldn’t belong to gypsies without attracting the scorn and disdain of Brahmins, he could only ride the bicycle after sunset. If he encountered an upper-caste man on the same path, he would have to dismount it promptly, as a sign of deference to their perceived superiority. The codes of servility were laid out and submitting to them was tradition.

Hardayal Singh had a textured, deep voice but he had never sung a song before in his life. When he joined the congregation in singing hymns, he sang raucously but with passion. In 1890, the Methodist Church in India published an Urdu hymn book in Roman script titled A Book of Songs of the Hindustani Church, which included hymns, bhajans, ghazals and Sunday school songs. Kneeling at the ebony pews of the Christ Church in Bareilly, Hardayal was joined by many new converts like himself. The lyrics were accessible in both Roman and Urdu scripts, and the tunes were mostly Indian. The acoustics of the church heightened each high note and the sweet smell of frankincense from the altar entranced worshippers into a divine reverie.

—

Regarding the present status of Bhantus, activist and film-maker Dakxin Bajrange suggested a social experiment for my next trip to Ahmedabad. He advised me to ask any rickshaw puller if they were aware of a ‘Chhara’ and if they would go to their area (Chharanagar). Wryly, he predicted that not only would the rickshaw puller decline to take me there, but they might also express disdain towards the Chharas and offer a cautionary word for visiting their area. Dakxin further notes that although Bhantus might be an invisible population on paper, if a crime occurs, the police would promptly arrive at their doorsteps.

Chharanagar today is a haven for criminals, where approximately 50 per cent of the local households produce illicit liquor under the supervision of law enforcement. In his book Vimyukta: Freedom Stories, Dakxin Bajrange emphasizes on the recurring cycles of crime and lack of opportunities that ensnare the Bhantus in India even today.

Excerpted from This Land We Call Home: The Story of a Family, Caste, Conversions and Modern India by Nusrat F. Jafri, with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Nusrat F. Jafri, is a Mumbai based cinematographer, with twenty years of experience in filmmaking. Born and brought up in Lucknow, Nusrat did her Masters in Mass Communication from MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia. Her latest short film, “Pilibhit,” starring Raj Arjun and Joyshree Arora, won her an IPTDA Award for the Best Cinematographer 2022, and a Critics Choice Award, nomination for the same film. She recently won the South Asia Speaks x Reportagen Fellowship 2025.