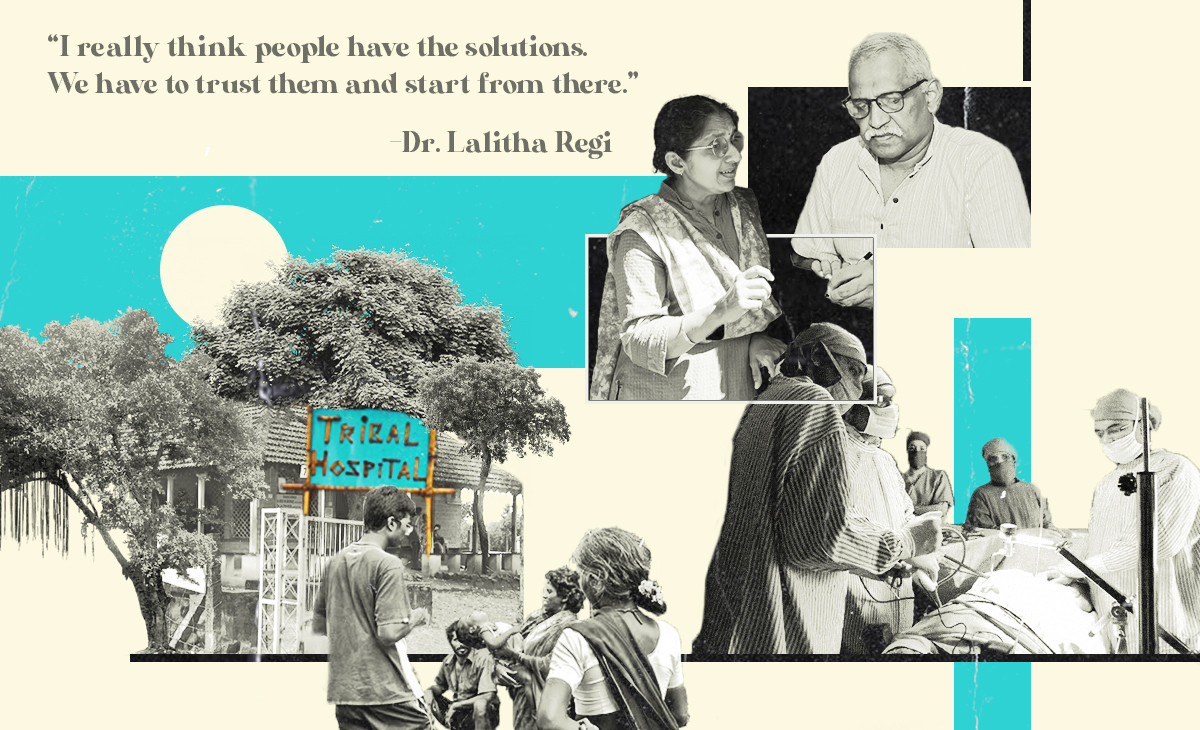

Tribal Health Initiative (THI) was started in 1992 by Dr. Regi George and Dr. Lalitha Regi. Medical graduates from Alappuzha, Kerala, the two backpacked across India in the early ’90s to look for a place that could use them most. They reached Sittilingi, a land of hills and Malavasis (‘Hill People’), with an infant mortality rate of 150, the highest in India.

They stayed. What started from a room and a 100-Watt bulb, is today a 35-bed full-fledged hospital equipped with an ICU and ventilator, a dental clinic, a labour room, a neonatal room, an emergency room, a fully functional laboratory, a modern operation theatre and other facilities like X-ray, ultrasound, endoscopy, and echocardiography. The THI is run and owned entirely by the tribal communities that today they also comprise its medical staff.

The Third Eye in conversation with Dr. Lalitha Regi, on what made THI possible and what we could all learn from it.

Could you tell us about Tribal Health Initiative, the organisation that you and Dr. Regi George started in Sittilingi, Tamil Nadu? What prompted this decision?

We started work here in Sittilingi Valley (Dharmapuri district) in 1993.

Back then, both of us were working in a hospital in Gandhigram, near Madurai. Regi is an anaesthetist by training, and I am an obstetrician gynaecologist.

Our work was fulfilling but we always wanted to do more and move beyond the precincts of hospital care. So, we left our jobs and visited many grassroots organisations to understand how they work on various issues, not just health. We also had a chance to go to several tribal areas. We realised that tribal areas all over India are geographically isolated, so nothing reaches there. None of the government programs, or for that matter, nothing close to a scheme; a development plan ever reaches the people there. We knew that here was a large gap to fill.

We looked at the health statistics of Tamil Nadu and shortlisted three places which were farthest from any healthcare facilities. Sittilingi happened to be one of them. So we came here first and settled down. Initially, it was only us in the team. And then two friends of ours – an engineer and a health worker – also joined.

We knew that we had to work on other determinants to improve the overall health of the community. But when we came here, we realised that the nearest resident doctor was 48 kilometres away and if people had to go for any surgery or in case of a medical emergency, the nearest medical facility was 100 kilometres away. There were no buses for 14 hours in a 24-hour cycle! We knew that there was a need for a hospital here more than anything else. You can’t talk about other things when people are dying.

We started as a small outpatient facility, which grew over the years to a 10-bed hospital and now has 30 beds. It is a secondary-level hospital. The uniqueness of our hospital is that 95% of our team comes from the community – our local tribal women and men who got trained with us. All of our nurses, pharmacists, lab technicians, administrative staff, drivers, everyone is from the valley and the two hills that are around us.

We also run a community health program in 26 hamlets in two valleys. Both of these also have tribal populations.

Given that your own practice is deeply rooted within communities, how would you define public health?

I’d say it is about looking at health from a larger perspective, from the point of view of communities and not just individuals.

The public has to be a part of this dialogue around health. When you plan or execute something, you have to listen to what people and communities have to say, how they articulate their needs and how to address them. I feel that is the way public health has to happen.

In a lot of places, this perspective on public health doesn’t exist at all. So, unless the needs of every disadvantaged community, the minorities, people with diverse socio-economic challenges from every nook and corner are not listened to and addressed, we cannot say that we have a good system. I’m not saying that these processes have not happened at all. They may have, in pockets. But there is a lot more to do.

Could you tell us a little more about your community health program and local participation?

Initially, we trained young women from the village to be health workers. They had studied till Class 8, because that’s all that the government school here offered then. Gradually, they studied further through correspondence.

In the beginning, we had thought that these young health workers would work within the community. But then, the hospital began to grow and no trained nurse or paramedic wanted to come here and work. So, all these young girls from the community began to staff the hospital.

We realised we still needed more people. So, in the course of three to four years, we trained more people from the village, whom we call health auxiliaries. These people are in their 50s and 60s, my generation. Some are older also. Most of these men and women are farmers. They have never been to school, because there was none when they were growing up. Our curriculum and training, whether for the health workers or the auxiliaries, is very participatory. We listen to them intently. What are their problems? What does the community need? All this is part of our curriculum, the things we all have to learn about. The training was very local, based out of our Tribal Health Initiative Centre, so that the people could continue with their farming, while devoting some days in the week to the training.

In about three or four years of work, they brought down the infant mortality rate. It was 147 here when we came. Now it has come down to 20. Maternal mortality also became nil.

It’s amazing to see a community-managed reduction of infant mortality. You spoke about other determinants that influence health. Could you please elaborate on this because often we end up seeing things in isolation?

Yes. So, like we knew that agriculture, nutrition, livelihoods, people’s own understanding of rights and good local governance, all these are very much a part of health. After 10 years of work, in 2004-’05, just around the time we had the tsunami, we thought we must move to the next level. We can’t just focus on the hospital and community health programmes; we should try and address other larger issues also that are linked to the wellbeing of the community.

And so, naturally, like always, whenever we are in doubt, we go back to the community. We know that no matter what, when you are working for any community, the people have to have the final say. We did a padayatra in the valley. We closed the hospital for three days a week: only core emergency staff stayed back. As a team, we walked to the villages. We visited every single household, and called everyone for meetings in the evenings. We’d sleep in different villages and then move on the next day. We said we are here not to talk about illness or about the hospital, but to discuss about health in a broader way. Do you think you are healthy? If not, what do you think are the causes for your bad health? Can we seek solutions together?

We did this yatra for several months. And because we went to every single household, everyone participated in our meetings and spoke openly to us about a lot of things – lack of schools, transport, other facilities, alcoholism.

But in every single village, they talked about agriculture. It’s not as if people don’t realise that agriculture is linked to health. They said – knowingly or unknowingly – we have gone into a different kind of agricultural system with increased dependency on chemicals and fertilisers. Because of this, we are all in debt, and don't know how to get out of that indebtedness.

They also said, we are not eating the food that our elders were eating earlier. And we know that we are not as healthy as them. So we know all this, but we don’t know how to come out of this cycle.

We said if this is how you all feel, maybe we should have some farmers’ groups where we can talk about these issues. A few groups came up. After two years, four farmers came forward to try organic farming. Now there are 500 of them, all members of Sittilingi Organic Farmers Association. These are all small farmers with one to three acre land holdings each, but together as a society, they have become a producer company.

Their central premise is that the food that they grow must first serve them and their families so that they can be get appropriate nutrition. The surplus is sold at premium prices since it is organic. The women’s groups have done a value addition to this – they make products from the farming surplus and that gets sold in organic markets. So basically, these farmers, not all of them, but the 500 who are part of this initiative, have become food secure and nutritionally self-sufficient.

It is important to think of health in these ways. We don't see anaemia during pregnancy here now. Of course, there are women who have migrated to cities and come back here for delivery in the tenth month. They may be anaemic, but not women who are in the valley.

It is not just a question of getting proper iron and folic acid, though that is important of course. It is mainly because of the food intake, which is sufficiently nutritious. It is not expensive food. Small farmers grow millets that have high nutrient value and all the uncultivated greens that come in rain-fed farming, and then other vegetables and greens and local fruits. All these help in preventing malnutrition in children and anaemia in pregnancy.

There seems to be an almost direct relationship between change in farming practice and better health indicators. Have you looked into this in more detail?

We haven’t done a systematic study on this, but we have seen some bad trends in health statistics here in the valley over the years, when, say, other kinds of food comes in or when people migrate in search of work and their diet changes. There is deterioration in their health along with arrival of non-communicable diseases… those things that were not there earlier. And increase in malignancies. All these we have seen over 23 years.

We are 100% sure that food is directly linked to our wellbeing and health.

There are certain knowledge systems that already exist in communities, but there is also a huge push for modern medicine. Since you are both doctors, how have you negotiated a balance between the two?

When we came here, the traditional herbal medicine system was already disappearing. We believe that there is no one perfect system. For surgery, you definitely need allopathic interventions. For some others, other kinds of medicines may work better. This is our personal understanding. We have always respected traditional medicine. Like, if the villagers want to bring in a temple priest and do some rituals here around a patient, we participate. Because we respect their customs. And because they respect what we do. What is important that the patient should become all right.

What have been in your experiences around the pandemic? How did the community handle Covid?

We didn’t have Covid cases here in the first wave. Villagers made their own masks. And of course, our community health team was with them. Local governance becomes very important when something like this happens, and we have a very good panchayat. Our president is a former health worker; she is very proactive.

In the first wave, different villages did different things. They didn’t allow outside people to come in. Villagers didn’t go out. But during the second wave, people were less careful. So we allocated 15 beds in the hospital for Covid care. Some volunteers and young people did a lot of awareness generation. We had a helpline where people could call and clear their doubts. So whatever cases we had, we either managed through home quarantine, or at level two, in the hospital. It was a collective effort.

Are there any particular insights around gender interventions that you would like to share?

We were often asked why we didn’t speak to people about sterilisation and small family sizes. See, the thing is that as under-five infant mortality rate started coming down here, people started approaching us for sterilisation on their own. People are not stupid. They want small families.

But if the infant mortality rate is so high, then it seems better to have five children, in case you lose some in childhood. So why would you do sterilisation? But once the children started surviving, people themselves came forward.

So generally it is said that communities are not aware, especially the poor and the marginalised don’t know anything – all this is not true. If issues are addressed, then people know how to pick the best solutions for themselves.

If you could make an ideal policy document on public health with recommendations from a feminist point of view, what all would it include?

What is needed has to come from the people and especially women. The women know what is needed in the family, how to make proper allocations, how to prioritise and so on. Then, it has to be a panchayat level planning as each place and context is different from the other.

You have to listen to people, the needs of the community and then plan solutions. The approach has to definitely be interdisciplinary. Health is a very misunderstood term. People think it is only about management of illness. But the promotion of holistic health and wellbeing and prevention of illness are interlinked.

Also, you must include the disadvantaged people, say the aged, or physically challenged in this dialogue. It is only then that one can develop equitable healthcare.

I really think people have the solutions. We have to trust them and start from there. Any community whether it be rural, urban, tribals, Dalits anyone can actually make changes. That’s my learning.

And I think the government should make things work. Ideally there should be no need for THI here. Government systems should work.