Read part one here.

The development of Urdu prose and journalism and the parallel agenda of social reform in 19th-century Hyderabad played a vital role in setting the ground for the emergence of the Progressive Writers’ Movement a few decades later. The aims and objectives of the Progressive Writers’ Movement (PWM), which began in the 1930s in North India, resonated with students, poets, writers and scholars in Hyderabad. The PWM urged writers and poets to organise and break away from the hackneyed tropes, themes and genres of classical, romantic poetry that had dominated the literary milieu of Hyderabad and were associated with great cultural capital. Instead, the PWM wanted to create a new, more meaningful aesthetic that would represent changing political and social conditions and confront the material realities and experiences of everyday life. Apart from class struggle and class injustice, which was a major concern for the PWM, progressive writers also stressed the need to fight for political freedoms, resist political repression, and forge grassroots connections with the people 1.

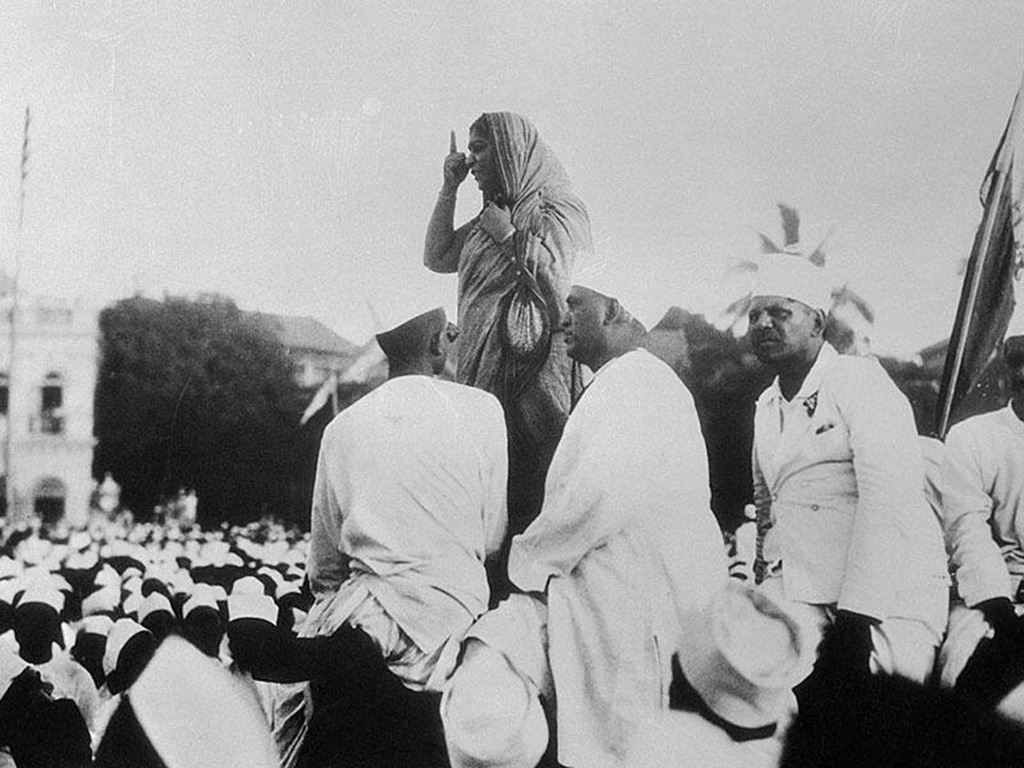

The Hyderabad chapter of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) was established by Makhdoom Mohiuddin along with Akhtar Hussain Raipuri and Sibt-e-Hasan in 1936. Sarojini Naidu offered her home, The Golden Threshold, as a venue for PWA gatherings and, later, for meetings of the banned Communist Party of India (CPI) 2. Among the women writers, journalists, intellectuals and activists associated with the PWA in the 1940s and 1950s were Jahanbano Naqvi, Zeenath Sajida, Rafia Sultana, Azeezunnisa Habibi, Brij Rani, Jamalunnisa Baji, her sisters Razia Begum and Zakia Begum, and Najma Nikhat. Amena Tahseen emphasises that the period after 1936 was critical for the history of women’s writing in Hyderabad because although women had been publishing their work, forming associations, and leading and participating in social, educational and literary initiatives for decades before the formation of the PWA, these endeavours were limited largely to women’s gatherings alone 3. The PWA changed this forever, and women began to attend and participate in literary and intellectual gatherings which had previously been restricted to men only.

The most vivid example and description of this shift comes from Jamalunnisa Baji’s autobiography, Bikhri Yaadein (Scattered Memories; 2008), which not only documents and assesses the political and literary events that took place in Hyderabad over the span of almost a century, but also furnishes information and reflection on what these events meant to women like Baji. Pardah is an important preoccupation in this account. Baji had long considered it her bane but had been unable to give it up. She describes how her younger sisters—who had had more freedom than her, were better educated, and were allowed greater choice in choosing their partners—had discarded the pardah at a young age. Literary gatherings with the leading Progressive figures of the day began to take place in Baji’s house in the 1940s on her and her brother Akhtar’s initiative. She had always been interested in literature and politics and was supported by parents and siblings who had an apparently insatiable appetite for education and literature. This drew her all the more to discussions that were happening beyond the curtain that separated her from gatherings where her sisters and other women who did not observe pardah, listened and spoke 4. Such gatherings offered her the opportunity to gradually emerge out of pardah.

The Progressive writers and the Telangana People’s Struggle

Between 1946 and 1951, the rural districts of Telangana had risen against the feudal structure of the Hyderabad state and the oppression it had wreaked on peasants and agricultural labourers for generations. The struggle began organically, with a tenant cultivator named Chityala Ailamma refusing to hand over her harvest to the landlord’s men. Within a few months, however, the Communist Party entered the fray and began to operate under the aegis of the Andhra Mahasabha, which had been formed in 1930 to champion the cultural and social rights of Telugu-speaking people. At its height, the Telangana People’s Struggle involved three million people from 3,000 villages 5. The struggle also made its way to the cities, as factory workers and students protested and went on strike. Many Progressive writers also identified as communists and were active members of the CPI. As the people’s struggle intensified in Telangana, the CPI was banned in Hyderabad and many PWA members had to go underground. So,

PWA meetings began to take place at Baji’s house at night, which was less conspicuous than the Golden Threshold, Sarojini Naidu’s house, and offered better cover to the likes of Makhdoom, who was well-known and easily recognised.

Baji formally discarded the pardah during the All-India Progressive Writers’ Conference in 1945, which was held in Hyderabad. She, her sisters, and one other woman were the only women to sit in the open with the men 6. What enabled the participation of a large number of Hyderabadis, especially women, in the Progressive movement was the PWA’s approach right from the start to not limit their membership to committed socialists 7. To be sure, there was always a core group of socialist writers at its centre, but the only expectation from all member writers—irrespective of ideological persuasions—consisted of them sharing the basic agenda of the manifesto, i.e. to build a sturdy organisation of writers who opposed reactionary social tendencies and stood for a literature rooted in reality. Indeed, so successful was this broadly defined manifesto that there were many writers who would not fall easily into this category if it had been ideologically restricted, but who nonetheless identified as Progressive and were closely connected with the PWM.

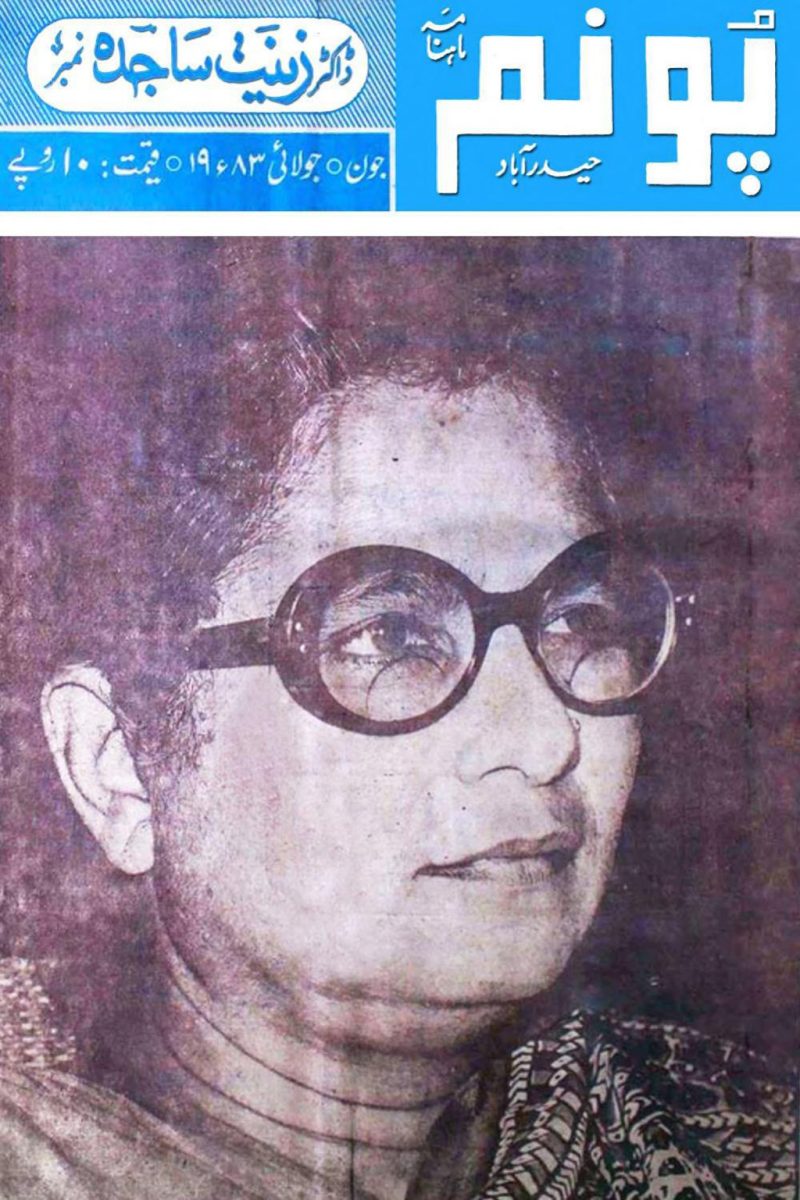

Zeenath Sajida (1924-2009) and a thriving culture of women writers

Zeenath Sajida was one such figure who dominated the literary and cultural circles of Hyderabad. She is a good example of a Progressive writer who not only wrote works criticising social injustices and exposing the hollowness of middle-class values, but also those that were less political and consisted of humorous essays as well as classic, romantic short stories. Sajida was most prolific in the decades spanning the 1940s to the 1960s, publishing an anthology of short stories in 1947 and several academic manuscripts on literatures of the Deccan. But the most fascinating literary writings she produced consisted of her essays in the genres of tanz-o-mizah (humour and satire) and khaake (pen-portraits), which were published in different newspapers and literary magazines and compiled only after her death in 2009. They cover subjects as varied as the gendered perspectives and lived experiences of women from different walks of life, critiques of social manners and everyday human folly, and nuanced documentation of the history and heritage of her beloved Hyderabad.

In the most political and radical of these texts, Sajida artfully and rigorously debates provocative social questions and taboos while disguising them in the genre of inshaiye or light sketches.

In these, she shows herself to be far ahead of her time, writing about things that we know today as gender fluidity, gender privilege, the mental load of women in relation to household management, the invisibility of domestic labour, and the unfair and unrealistic demands made of middle-class women professionals.

These essays also reveal the narrator’s most disarmingly vulnerable thoughts, feelings, and frailties; in the process, Sajida emerges as a writer who knows how to use emotion to extract both empathy as well as laughs from her readers.

There was a thriving culture of women writers of humour, satire and pen-portraits in Hyderabad right from the 1940s, which both received individual and institutional support from male writers and scholars and was also subjected to ridicule by them 8. Sajida’s work marks the best of this tradition of women’s non-fiction and is important to read and know also because non-fiction is generally neglected in favour of fiction and poetry, which have greater cultural capital; have come to form well-defined and durable stereotypes of Urdu literature; and, thus, capture the attention of translators, scholars and publishers alike.

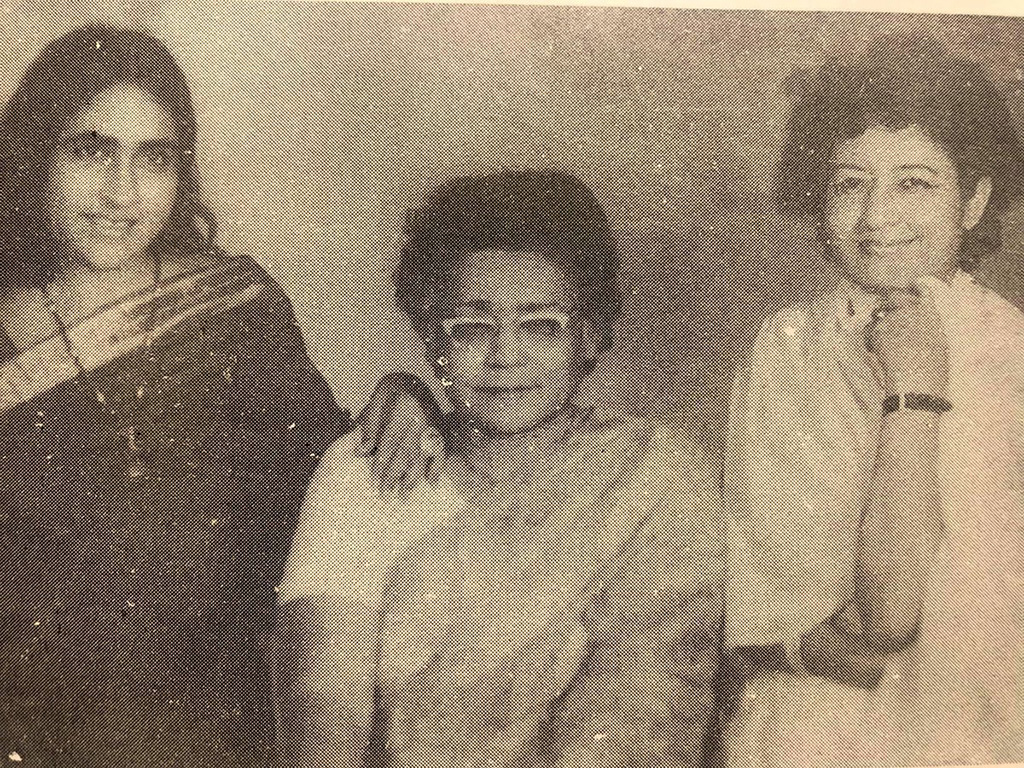

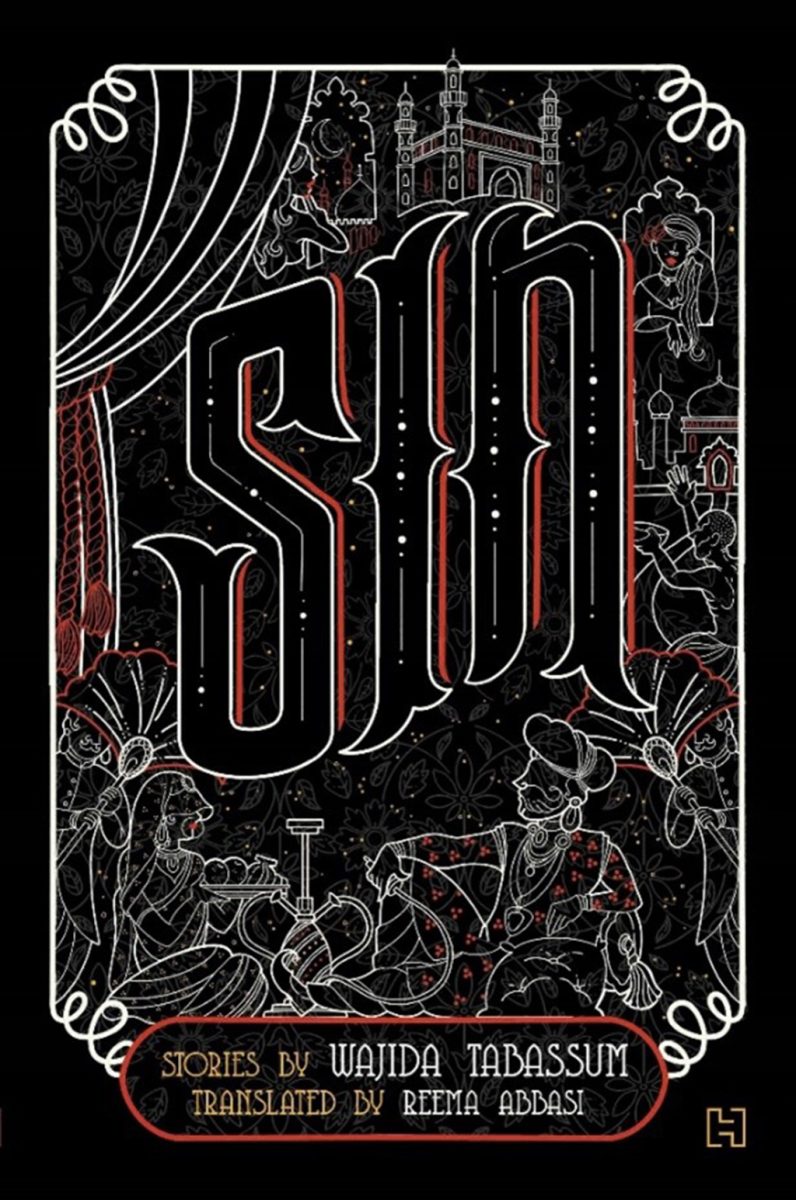

Among Sajida’s younger contemporaries were Jeelani Bano (b. 1936), Najma Nikhat (1936–1997), and Wajida Tabassum (1935–2011). Nikhat was a writer of short stories whose loyalty and commitment to the PWM exceeded the heyday of this organisation. Like Sajida, although Nikhat produced a relatively modest number of short stories, her oeuvre demonstrates skill and is important for its sustained engagement with her lifelong preoccupations and concerns. Her stories about life in the feudal deodis of Hyderabad are insightful and instructive in establishing how women of both working as well as upper classes lived and negotiated feudal patriarchy and the conservative social world of princely Hyderabad. She also wrote hopeful stories about the revolution and depicted the lives of the poor in the rural districts of Telangana and Andhra, where she lived for many years.

Although her many novels and short stories were successful and popular and the latter, in particular, are enjoying a resurgence of interest among youth after the Me Too movement, many Hyderabadis, including scholars, look down on her work as “obscene” and “unjust” towards the feudal aristocracy 9.

The “shock value” of Tabassum’s approach often belies her profound and nuanced understanding of the precise workings of culture and society towards concentrating and maintaining power in a few hands. Until recently, only a couple of Tabassum’s stories were available in English translation.

Other continuities

Over time, the PWM—its ideology and aesthetic—acquired a hegemony that ensured the marginalisation of writers who did not consider themselves Progressives. This became a big problem when in the tension between the “creative section” and the “political section” of the PWA (Progressive Writers’ Association), the latter prevailed, and this often resulted in didactic writing dominated by socialist themes and motivations 10. The ambivalence and even disenchantment of writers in other places towards the PWA, which increasingly adopted a rigid, even conservative stance towards the choice and treatment of themes employed by its members, is well known 11. But given that it had such a compelling social message, an influential platform, and an overarching visibility and influence, it is understandable that many women writers would continue to operate under the aegis of the PWA and utilise its many resources.

Other writers who did not subscribe to Progressive writing often represented literary and cultural continuities that were desirable and significant in other ways. After 1948, Urdu had been relegated to a secondary place in Hyderabad, and its resources and institutions were severely undermined by the minoritisation imposed by the new regime. Despite this, nuha, marsiya, azadari and salaam, traditional poetic genres that belong to the Shia practice of Muharram, continued to be regularly published in magazines and newspapers and also performed in ashurkhanas. Other religious or mystical genres, such as hamd and naat, and ghazals, nazms, and qasidas that did not represent Progressive thought or aesthetics persisted too. Many women poets wrote and published in these genres. Additionally, nazms for children were very popular in Hyderabad, and women were enthusiastic proponents of this genre as well 12. Often, these engagements revealed completely different ways of engaging with social and political discourses from Progressive writing, as can be seen in the way the poet Syeda Bano “Hijab”/Hijab Bilgrami juxtaposed the battle of Karbala with the struggle for freedom from colonial rule 13.

New woman, new writing

The next major shift in Urdu literature came with jadeediyat or modernism in the 1960s, which turned the subject of literature inwards and focused on the psyche of the individual, allowing for much experimentation in genre, mode and language. Some of the short stories and novels of Jeelani Bano and Rafia Manzoor ul-Ameen are good examples of jadeediyat from Hyderabad. Both wrote short stories and novels about contemporary protagonists struggling with the human condition as well as a variety of issues associated with the modern state and society. They also produced scripts and screenplays for successful TV serials, documentaries and films.

Rafia Manzoor ul-Ameen is best known today for her novels, especially Alam Panaah (Refuge of the World; 1983) and Yeh Raaste (These Paths; 1995), and the immensely popular TV series that was based on the former text and whose screenplay she wrote too. Both novels fall in the genre of romantic fiction and testify to her craft with language, narration, plot, and pace. The most attractive feature of this writer’s work is her psychologically and emotionally complex heroines, who represent a new world after the transfer of power in Hyderabad, in which young women were stepping out of the ostensible “protection” of the zenana, seeking education, professional employment and financial independence, and negotiating a society that did not appear to be prepared for their entry and often openly expressed its disapproval. These novels also offer multifaceted commentary on the social culture and ethnography of groups associated with Hyderabad and the Nilgiris respectively.

The significance of Jeelani Bano’s modernist writing can be appreciated from PWA co-founder Sajjad Zaheer’s comment in a letter to Sulaiman Areeb, editor of Saba (Hyderabad), that as long as Jeelani Bano is in Hyderabad, they need not worry about the Naya Afsana (New Short Story), a genre that had picked up pace in Urdu-Hindi literature in the 1950s and focused more on the inner state of the individual subject than on the external world or its ideological preoccupations 14. Over more than 50 years of writing, Bano’s nationally and internationally acclaimed short stories span three identifiable schools of Urdu literature: taraqqi-pasand adab (Progressive writing), jadeediyat (modernism), and tajreediyat (abstractism), although she has consistently refused to declare her affiliation or identification with any of these schools, explaining that there are many influences in her work and that she seeks only to represent the world around her and does not adhere to any particular ideological position.

Although some of Bano’s work has been admirably translated into English by Zakia Mashhadi, her two novels have not been given their due by English-language readers and scholars. Aiwan-e-Ghazal and Baarish-e-Sang represent the most serious and rigorous engagement with the history of princely and post-princely Hyderabad in creative writing. While the former narrates the lives of four generations of an aristocratic family against the backdrop of transformative change during and after the transfer of power, the latter represents the lives of landless tillers and labourers tottering under the weight of crushing debts in the rural districts of Telangana. Both texts offer rich and sombre insight into urgent questions of class and gender and offer a remarkable degree of depth where class, in particular, is concerned.

Radio continued to be an important medium for women’s voices in Hyderabad after the transfer of power, and the work of most Progressive writers in Hyderabad (and elsewhere) as well as those who did not subscribe to this category remained in demand. Among the many women who wrote for All India Radio (AIR) and read out their stories and essays were Zeenath Sajida, Najma Nikhat, Fatima Alam Ali and Badrunnisa Begum. Another vital development for women’s literary culture was the establishment of the Mehfil-e-Khawateen (Women’s Gathering) in 1971 at Urdu Hall (f. 1955), which became a flourishing platform for Hyderabadi women writers. Women poets of Progressive and other persuasions, such as Azmat Abdul Qayyum, Azizunnisa Saba, Ashraf Rafi and Muzaffarunnisa Naz, were instrumental in founding and running the Mehfil over the years. Monthly meetings and annual events are conducted and are well attended. The association also publishes an annual magazine.

Life-writing and auto/biography

Another important feature of Hyderabadi women’s writing in Urdu is an enduring affinity for different forms of life-writing. While Jamalunnisa Baji’s autobiography is the richest example, meaningful deployments of auto/biography emerge also in other genres that demonstrate a strong element of self-construction and self-performance, usually through first-person narration. The travelogues of Sughra Humayun Mirza and the humorous essays and pen-portraits of Fatima Alam Ali (1923-2020) are a good example of this trend. Fatima Begum grew up in an environment suffused with literary, political and intellectual discussions in the 1930s and 1940s, for her father was Qazi Abdul Ghaffar (1889-1956), the immensely popular and admired Progressive editor of Payaam. Her humorous essays were published in Siasat from the 1960s to the 2000s and also read on AIR. Some of them were compiled into a book called Yaadash Bakhaer (May God Preserve Them; 1989), which also furnishes a selection of her pen-portraits of the poets and scholars she knew. These portraits animate in words the rich and potent milieu of the mid-20th century and vividly perform and re-create the development of Fatima Begum’s own subjectivity.

Finally, scholar and translator Oudesh Rani Bawa (b. 1941) writes a weekly column, titled Mujhe Yaad Hai Sab Zara Zara Sa (My Blurred Memories of Yesteryear), in the Urdu daily Munsif, where she engages with popular and historiographical narratives of the past, filtered usually through her memories and research on the material and linguistic heritage of Hyderabad. She also uses this column as a platform for her political and social critique, and has, most recently, begun to actively criticise local and national events, with respect to government policies, heritage and development, and growing right-wing intolerance and violence.

Hyderabad continues to have a thriving culture of humorous writing among women in both prose and poetry, besides other modes of writing, such as the short story, novel, novelette, plays and ghazals.

- Ali Husain Mir and Raza Mir, Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry. New Delhi: Roli, 2006, 4-6.

- Rakhshanda Jalil, A Rebel and Her Cause: The Life and Work of Rashid Jahan. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2014, 289-90.

- Amena Tahseen, Hyderabad mein Urdu ka Nisai Adab: Tahqeeq wa Tarteeb, Delhi: Educational Publishing House, 2017, 2017: 9.

- Jamalunnisa (Baji), Bikhri Yaadein, Hyderabad: Idara-e-Fikr-o-Fan, 2008: 85.

- Stree Shakti Sanghatana, We Were Making History: Life Stories of Women in the Telangana People’s Struggle, New Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989, 3.

- Jamalunnisa 2008: 103. Op. cit.

- Ordinary Hyderabadis were suspicious of communists because they were all thought to be atheists. Ibid. 121).

- Habeeb Ziya, who is a humourist herself and has compiled and edited a collection of Hyderabadi women’s humorous writings, reveals that Mujtaba Hussain, the most prominent and celebrated humourist from Hyderabad, had criticised her article on Hyderabadi women’s humour in the Siasat newspaper. He had wondered if men are supposed to sweep and mop, while women write humour in large numbers. Ziya Hyderabad ki Tanz-o-Mizah Nigar Khawateen. Hyderabad: Shagoofa Publications, 2005, 7.

- See e.g. Ashraf Rafi, “Hyderabad ki Afsana-Nigar Khawateen,” in Tahseen 2017: 173.

- Mir and Mir 2006: 28. Op. cit.

- See Ayesha Jalal, The Pity of Partition: Manto’s Life, Times and Work across the India-Pakistan Divide, Noida: Harper Collins, 2013, 162–72; Jalil 2014: chapter 7; Mir and Mir 2006: 33.

- Tahseen 2017: 136. Op. cit.

- Riyaz Fatima Tashhir, “Hyderabad mein Khawateen ki Rasaai Shayari,” in Tahseen 2017: 219.

- Mosharraf Ali, Jeelani Bano ki Novel Nigari ka Tanqeedi Mutala, Delhi: Educational Publishing House, 2003, 21.